After a couple articles were recently published in HuffPost about my own smartphone sabbatical and my choice to not let my kids have devices, many readers reached out to me. Most wanted me to know they didn’t have a smartphone, or they took smartphone sabbaticals themselves, or they too didn’t let their kids have devices.

I noticed in myself a bizarre aversion to those statements. Every time someone reached out to connect with me, I felt less connected rather than more. With each message all I could think was, “That’s not the point at all.”

Of course, based on those articles, my aversion to these readers’ responses made no sense. The articles were obviously about technology, and the reader responses were precisely what they should have been. But I do not want to talk to people about the methods by which they engage or avoid technology. I’m not judging anybody, and I definitely don’t have a perfect strategy here.

I had to think about it for a while, but I’ve come to realize that I did not like talking about the phones because, in my mind, they are almost entirely beside the point. After all, two people can keep smartphones from their kids for wildly different reasons, and two people can give smartphones to their kids for wildly different reasons.

No offense to HuffPost, but what I really wanted to think about in those pieces was not the devices themselves. What I really wanted to think about is the kind of people we—all of us—are becoming.

It’s hard to do that in 900 words, which is why I have a Substack.

Let’s back up. When I became pregnant for the first time after years of fertility treatments, I swore off all medical interventions for my imminent delivery. I never again wanted to be prodded, injected, or even examined. It’s a long story, but all that matters here is that, in the end, I gave birth to a baby all by myself. Which is to say, I cannot remember the midwife’s last name because (a) I didn’t like her very much and (b) I’m not sure she ever even touched the baby.

This is not an essay about the right way to have a baby. However, to make the point I want to make, I need to confess that I think having a baby without medical intervention significantly changed my life in a positive way.

I am hesitant to tell other women this for obvious reasons. People would rather talk to the new vegan at the party than the woman who just triumphantly finished a natural childbirth and probably also ate her placenta.

But it’s been twelve years now, and I can tell the story unclouded by emotion or any sense of pride. I am being as objective as I can be when I point to my first delivery as a watershed moment in the make-up of my current self.

I once wrote, privately, about giving birth to my first child. Here is a small excerpt from that piece:

As the chair rolled toward the elevator, I winced at the hairline seams between the vinyl tiles, agony in millimeters. When I could not go any further, I raised my right hand, just barely, from the wheelchair’s armrest, and my husband stopped. When the worst of the contraction had passed, I lowered the hand, and my husband eased the chair forward again. I did not moan or yell or sob; I would not dare use energy I needed to breathe. I don’t know how he knew that the hand meant I needed him to stop.

We made it maybe three hundred feet this way; maybe it took five minutes, maybe an hour. Upstairs there was paperwork; there were clipboards. My husband tried to explain it was too late for all that, but the women in scrubs, the ones who knew better, said it had to be done. I could not make out words on the page, could not tell where I ended and the room began. I closed my eyes, boring into the darkness, getting as far away as I could from the voices. The pain was magnificent, a force field. The pain rolled me into the tiniest ball, no bigger than a marble. No one listened as my husband explained that I’d been in labor for hours, that the contractions were now seconds apart. But then, in the wheelchair, from wherever I had gone in the darkest dark, lightyears away, I started pushing. The noise of the hospital was nothing to me. I was totally alone.

Before I gave birth, my midwife told me that, during some point in labor, I would think I was dying. “You won’t die,” she said. “But you’ll think you’re dying.”

She was right. Even so, I knew what was happening (the baby being born) was supposed to happen. Rarely are instances of extreme pain marked by that kind of comforting knowledge that all is well. That kind of pain (pain entirely distinct from trauma) transforms a person.

I have come to think of that delivery experience as a portal. I entered it unprepared to become a mother and left it more prepared.

The reason for this is that I didn’t think I could do it. I didn’t think I was the right kind of person to give birth naturally. I didn’t think I was brave or strong or healthy enough. Only under that extreme post-IVF circumstance could I have convinced that inexperienced, fearful version of myself to deliver a baby without help of any kind.

I didn’t think I could do it, but I did do it.

I thought I was dying, but I didn’t die.

Someone else might point to the transformative experience of running a marathon or jumping off a high dive. There’s something undeniably life-changing about doing a thing you are certain you cannot do, even if the only change is that some invisible-to-you neurological pathways are forcibly rewired.

I can point to another transformative time that was painful but not traumatic: the years that came after that childbirth and two more, when I found myself the mother of four children four and under.

Had you seen our 2016 Christmas card, when our infant twins were flanked by our adorable toddlers, you would have thought I had everything I ever wanted. You would have been right.

Also, I was being ground to dust.

One morning I stood on stairs outside the big kids’ preschool, balancing two impossibly small babies in two separate car seats while two toddlers ran toward traffic. I did this all the time, but on this particular day, I collapsed onto the concrete stairs and wept, just around the corner of the building where the other mothers couldn’t see. The toddlers kept running, the babies kept crying. I stayed on the stairs sobbing for a long time, but I never told anyone.

Most days, I held it together. I was happy at the same time I felt I was being erased.

The kids’ preschool teachers always said to me, “I don’t know how you do it!”

I didn’t know either. I would drive away in my minivan and think to myself, “I am dust.”

During those years, I remember chanting phrases to myself. “You are not going to die.” “You are stronger than you think.” “You will do this because you have to do this.” Four children were always screaming their need for me—only I would do—and my nerves had been sandpapered off at their tips. But I would breathe very deeply and help the children one at a time because they were all I had ever wanted in life. And I knew the kind of “pain” that was happening to me was a good kind. It felt like annihilation of the self but also, somehow, like love.

More than once, doing the thing I was certain I could not do has changed me.

It is, of course, complicated. Pain outside the context of love and choice is trauma, and we know it causes unbearable, physiological and psychological damage. There is pain that destroys and pain that transforms. If we don’t make this distinction, it is easy to forget that not all pain is bad.

If we don’t remember that not all pain is bad, we will go to great lengths to avoid it. Technology (which has always been, essentially, just a way of solving problems) is always waiting in the wings, willing to step in to save us.

In a recent manifesto written by the OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, he views life as a problem that AI alone can fix. If you think I’m exaggerating for rhetorical effect, go read it yourself.

The Sam Altmans keep promising us ease. Just around the next corner, the machines are going to make life so effortless, so convenient, so slick and smooth we’ll never have a day of pain. People in tech talk about finding “pain points”—say, having to answer the door when your food is delivered—and coming up with technological workarounds.

Mark Zuckerburg is very fond of the word “frictionless.”

If you think all pain is a problem, you are right to avoid it.

Andy Crouch, a writer I’ve loved for a long time, recently wrote here that we modern Americans are “unformed as people.” In other words, we are lacking character development. If we want to be formed—something more than useless hunks of marble—we have to hold still while someone takes a chisel to our face.

Only an idiot would choose a chisel to the face over convenience, right? I would love to have had a machine that carried all four of my children while I walked happily into preschool, my hands wild and free.

I have to really think hard about my life to know that I am sure I do not want to be the person I would have been without pain. These days I am still selfish and ornery, but I am much braver. I am much stronger. I am much, much freer.

Because of pain.

Not wishing to avoid all “pain points” in my life is only one reason I am skeptical of my smartphone and the Sam Altmans of the world (whose voices, I promise you, are about to get louder and louder). In addition to the development that is the result of friction (quite literally, chisel against stone), I think over-reliance on technology can separate me from other meaningful things like silence, boundaries, and beauty. In short, I think technology is full of false promises.

All those days when my kids were really little and I was silently chanting, “this is impossible,” I also had another voice in my head. That voice had arrived only recently, when I gave birth after enduring the trauma of infertility. The new voice said, “You did not think you could do that other thing, either. But you did.” It said, “Sometimes pain is good.” The voice was pain transmuted, offering me a different kind of promise.

I had, during those difficult years, the distinct impression I was being “formed.” I now realize that’s what I meant when I thought, in my sleep-deprived and addled mind, “I am being ground to dust.” A new thing was being made.

When we are unformed, Crouch writes, we over-rely on the magical promises of convenience and ease. By over-relying on convenience and ease, we fail to become formed. It is a cycle that promises to keep us just the way we are.

Applied to children, painlessness promises to keep them children—their whole lives.

Applied to a whole society, painlessness promises to keep us inept and indignant, stuck in cycles of learned helplessness.

These days I don’t feel that I am in any sort of crucible. Nothing miraculous or meaningful is happening to my soul behind the scenes of my life. I am working and watching some bad television and generally embracing this time of non-formation, all chisels safely distant from my face.

Even if no other big, transformative pain comes for me the rest of my life, our days are filled with little trials. No amount of technology (sorry, Sam) is going to change that fact. If we think the trials are bad and unfair—that pain is out to get us or the system is malfunctioning—we will live in constant misery.

If we can, as Crouch suggests, view the daily pains as formation—pain that hurts even as it whispers “all is well”—we can be changed.

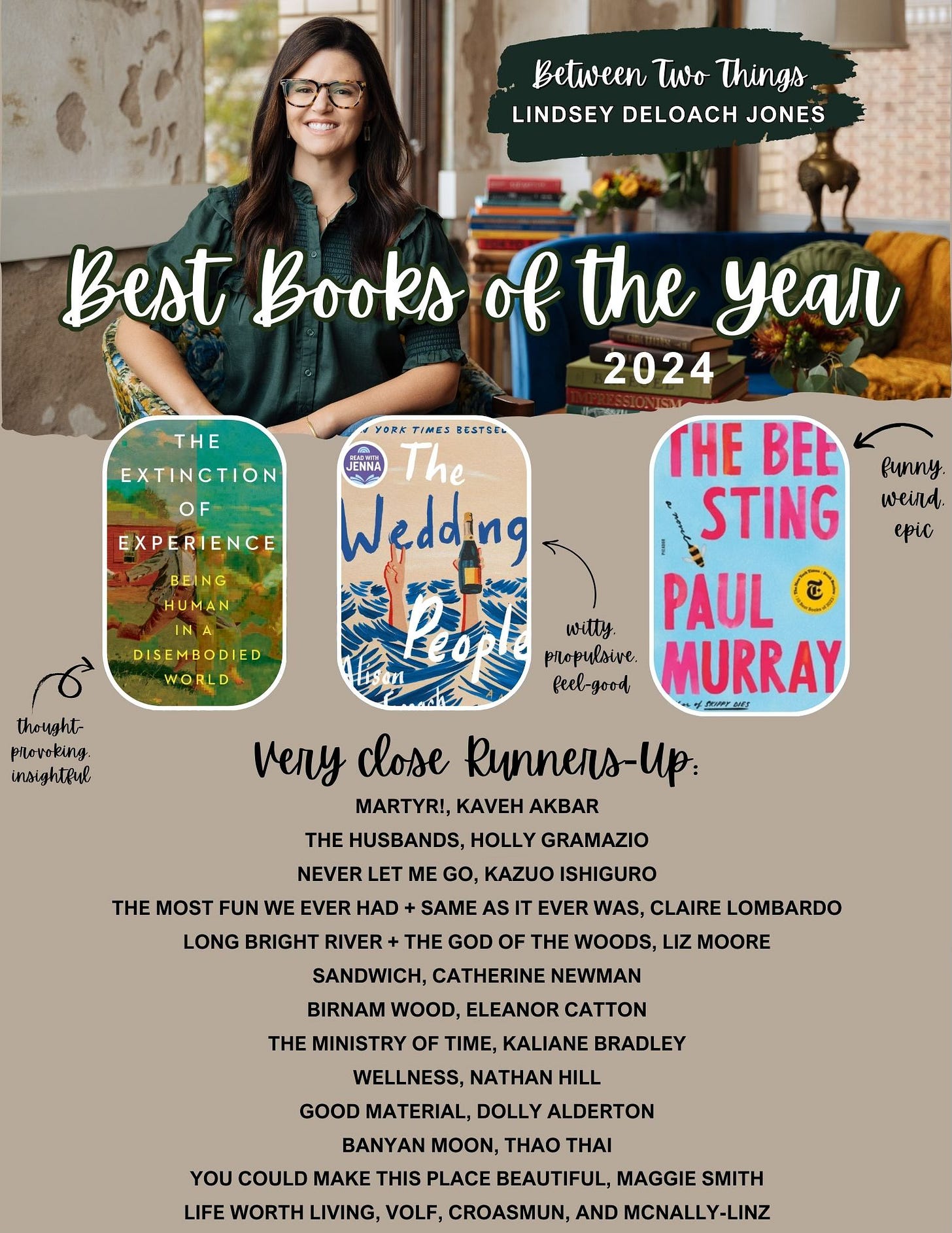

P.S. Here’s a little freebie: a printable list of my favorite books of 2024! Which ones have you read??

Absolutely beautiful essay, Lindsey. When I got sober, I truly thought I might not be able to survive the pain that rose to the surface, which I had been drowning in alcohol and distraction for so many years. But I did indeed survive, and realizing that I could withstand my own pain gave me the confidence and fearlessness I always thought alcohol was giving me. Pretty wild.

I haven't even finished this essay yet, but I have to relate to something you articulated so well. I received a life-changing diagnosis about five years ago. Before that, I had lived for years with crippling anxiety, but I sometimes talk about my diagnosis as something like being shocked by a defibrillator. I was dead, and then I was alive. I had lived for years afraid that something might happen to me that I couldn't survive. But then the thing happened - the thing I thought I couldn't do - and I did it. It rewired me. It changed everything. In nearly every way, it healed me. Thank you for saying it so well.