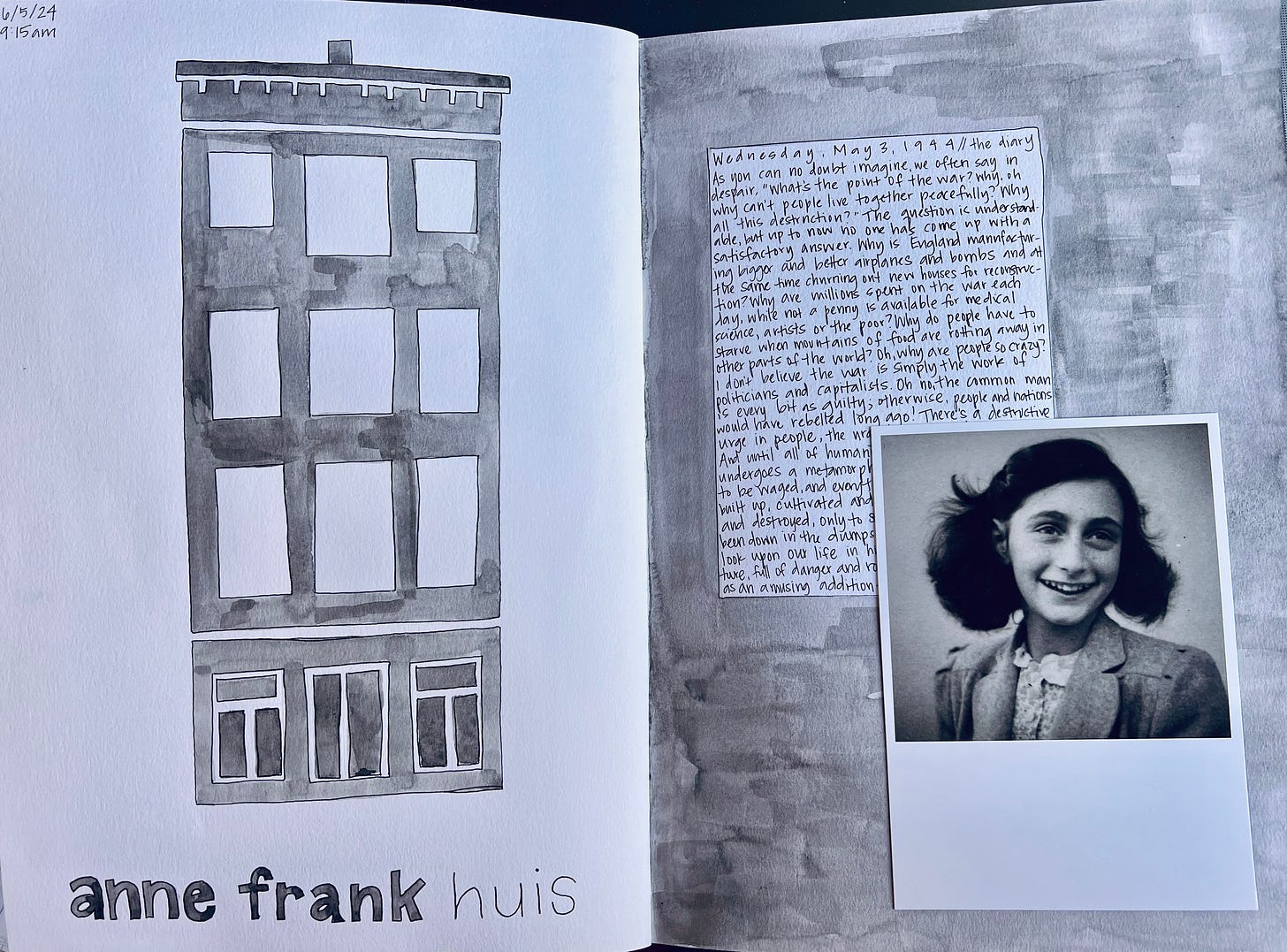

Wednesday morning I stood inside a wallpapered bedroom, charmingly vintage, thirteen feet by nine feet. Onto the wallpaper were glued photos, cut from magazines, of twentieth-century movie stars. Standing in the room felt like being underwater—pressure in my ears and behind my eyes, dim light, the feeling of separation from the rest of the world.

It was a writer’s room, the room of a girl barely older than my daughter. Anne Frank.

The emerging science of epigenetics tells us our experiences rearrange our bodies, all the way down to our genes. There must be a counterpart for physical places—the way a space can remember what has happened there. The air inside Anne Frank’s hidden bedroom felt solid, as if the oxygen molecules trapped bits of her life—terror, boredom, rapture—and held them aloft, like a story we could breathe in.

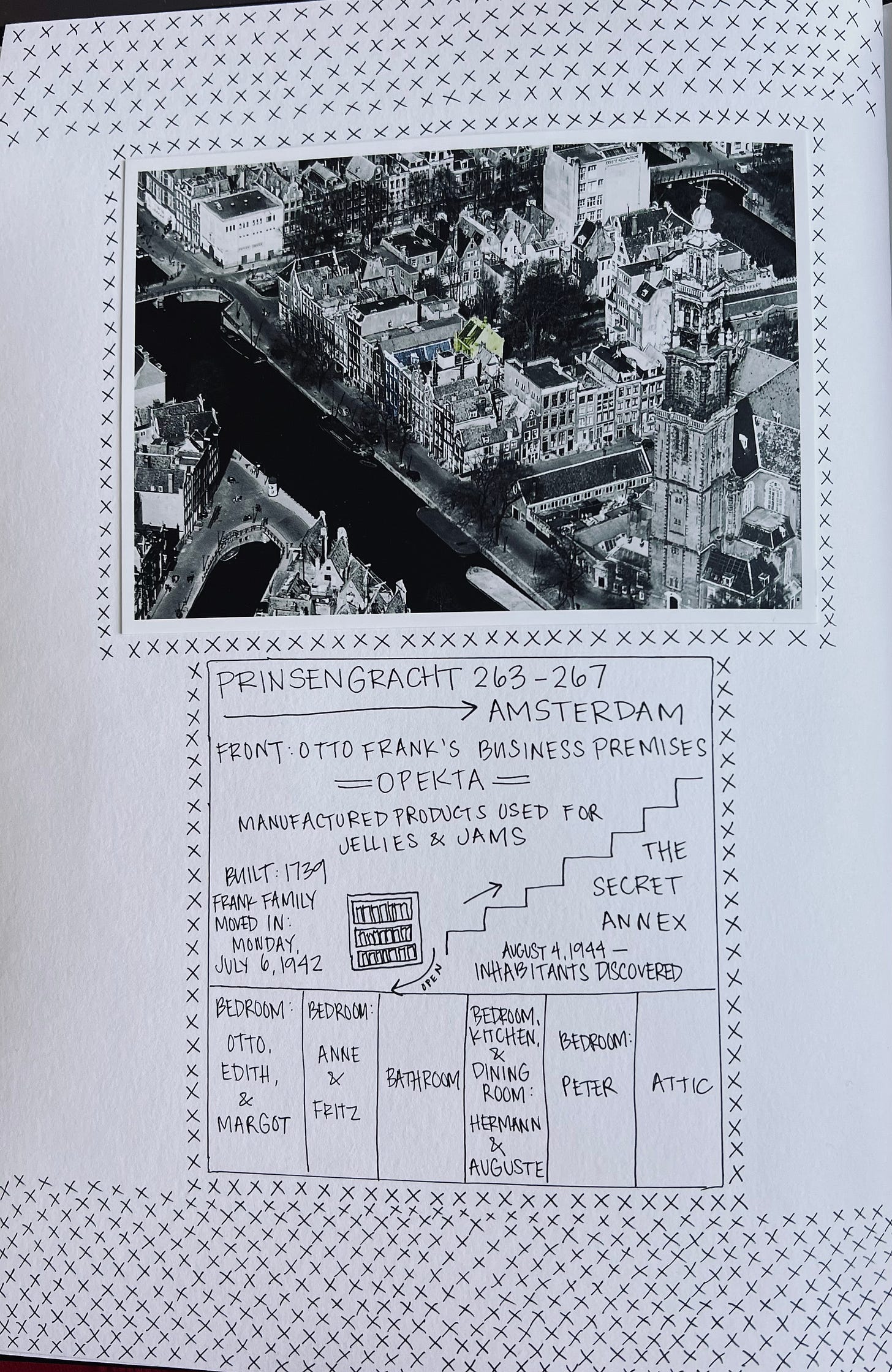

Or maybe the air was weighted by the sighs of the millions of visitors passing through since August 4, 1944, the day Anne was released from her hidden quarters into the fresh outside air, the first day in over two years she saw a bird or flower—only to be loaded like cargo onto a train screeching toward Auschwitz. Inside the bedroom, eighty years collapse; past and present blur.

For the first time since eighth grade, I re-read Anne Frank’s unabridged diary, finishing it my first day in Amsterdam. In eighth grade, I read from the vantage point of Anne, the thirteen-to-fifteen-year-old annoyed by her mother, in love—fleetingly—with a boy. I lacked all context for the narrative; I could not distinguish between eighty years and eight hundred. Now, I read like a mother, a woman who, unlike Anne, made it past fifteen. I read with the understanding that 1944 was yesterday. I read half the diary in Amsterdam and half back home, in a nation I firmly believe is on the brink of institutional collapse.

I hate that the rooms of the house lead, inevitably, to a gift shop. Still, I buy On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century. I stay up late reading, next to the window from which Anne’s Annex is almost visible.

Historian Timothy Snyder says this is how we avoid authoritarian rule: Make eye contact with people. Have a rich private life. Travel and read books. Be angry when someone misuses language.

Stand out.

After World War II, Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted an experiment to understand Nazi atrocities, in which participants were instructed to press a button to shock someone on the other side of a window. They did as they were told. Even when the people pounded on the glass, complained of heart pain, begged them to stop, they did as they were told. Even when it appeared the person on the other side of the glass had died, they did as they were told. They pressed the button—again, again, again.

My sister says I held up the crowd of people a couple times, staring at something on the wall. I don’t remember that. I do remember thinking, “This moment is changing me.” Maybe all the way down to my cells.

Wow, I have chill bumps all over, Lindsey. Your words beautifully convey how powerful this experience was.

In case I forget to tell you when you get home, please make a note to watch A Small Light (if you haven’t already).