Almost two weeks ago, the Supreme court of Alabama issued an unexpected ruling: frozen embryos created via IVF are legally to be considered children, and families and healthcare workers can be held liable for their destruction.

The ruling was made in response to a wrongful death lawsuit filed by grieving couples whose frozen embryos were destroyed in storage. As a person who is deeply invested in this conversation, for reasons both personal and philosophical, it’s been a weird experience to watch as, overnight, an issue that has stolen countless hours of my own sleep became the topic of dinnertime discussion in households across America.

Incidentally, one reason you haven’t heard from me much here at BTT lately is that I happen to be working on a project that aligns exactly with that debate. It is the culmination of a decade of research and soul-searching. Long before the court’s ruling, I was reading every book I could find on the topic, and I can’t count the pages I’ve written as I’ve grappled with this issue from every angle. Are embryos alive at the morula stage? After blastulation but before implantation? Before freezing but not after? What kind of rights do the “parents” of those embryos have?

To listen to the debate around IVF embryos as it plays out in public discourse has been painful for me. I can hardly listen to the podcasts and read commentary on the Alabama ruling. It takes me back to the difficult and lonely process of IVF. Even worse, it takes me back to a time in my life when the inability to answer with 100% certainty what I’ll call “the question of personhood” opened a chasm of fear and confusion that it took me a decade to recover from.

As always, I’ll reserve the details of the debate for in-person conversation. (If this seems to you like a black-and-white issue, let’s get coffee. I have some stories to tell you.) After many years, books, and conversations, I have reached my own careful conclusions, ones I think it would be unproductive to share on the internet.

As always, what interests me most (for the purpose of this newsletter, at least) is not the problem itself but the way we think about the problem. In fact, the question of personhood is mind-numbingly complex, capable of opening ALL the cans of worms. For a decade, my life was a worm-can-opening extravaganza.

When precisely does life begin?

Any attempt to engage the question of personhood forces engagement with further questions of science, faith, religion, politics, family, and philosophy.

You see, once the worms wriggle their way out of the bait can, the top’s not going back on. It’s just... worms everywhere.

Of course we can’t answer all those questions. Not even someone willing to stay up way past her bedtime combing through articles in medical journals can come close to attaining all the knowledge she’d need to answer these questions with certainty. IVF may be new(ish), but the questions raised by artificial reproductive technology are the basis of the most vigorous debates throughout human history.

Here’s the thing.

When confronted with complex issues, any weaknesses in our thinking and gaps in our understanding become apparent. We find ourselves feeling a bit unmoored, our inadequacies brought to the fore, vulnerable in the sudden awareness of our frailty. Then one of two things tends to happen. One: We revert to our simplistic understanding, doubling down on certainty. Two: We push into the discomfort.

Route one requires that we deny our own sense of unease. That makes for a quick and tidy resolution, one that ensures we can continue with our former alliances intact. We do not risk losing community... or losing face... or losing sleep by confessing our uncertainty.

I’m interested in the consequences of these tiny, daily denials. Each time we feel confused—or just a subtle spark of wonder, maybe—and choose to double down on certainty, we reinforce a sort of false knowing. I’m convinced these mundane choices erode a person’s connection to the truth, little by little. The space between Question and Answer gets smaller and smaller. Eventually the space is so small, we don’t even have questions about complex issues anymore. Certainty is second nature. We become answer factories, our hands perpetually raised like cocksure schoolchildren.

At the same time, we become less practiced at humility—the kind of desperate, visceral humility I felt glancing at my niece’s precalculus textbook last night. (Wow, I am not up to that cognitive task.)

Wanna know how I developed this theory? I spent a whole lot of time waving my hand in the air, bursting with answers. I didn’t push into uncertainty; I eradicated it. And then adulthood—that big bully—had enough of my hubris and beat the tar outta me, answers and all.

But there are two routes. Route two is pushing into the discomfort of our own inadequacies. It depends on the admission that the world is full of problems I can’t solve. It depends on curiosity. It depends, I think, on faith. It is uncomfortable and maybe embarrassing. It can be painful and frightening.

So why would we ever choose it? Well, we wouldn’t. I didn’t, at least not for a long time. Usually we don’t push into our discomfort until we’re completely surrounded by it.

But when I had no other choice, I found that route two (circuitously, because route two is never the shortcut) seemed to take me in the direction of truth, closer to reality. Leaning into uncertainty deepened my understanding, expanded my worldview, and fed my compassion. It made space for other people to exist outside the boundaries I had pre-drawn for them.

Hundreds of IVF cycles have been halted in the state of Alabama while IVF clinics figure out how to provide care without risking wrongful death lawsuits. When I heard a woman interviewed about her cancelled IVF cycle (after the tens of thousands of dollars had been paid, after the hormones had been injected), I felt sick to my stomach. I remember, when undergoing fertility treatments, days when I thought I couldn’t keep paying the cost. I remember, as the woman says, “days that felt as long as years.”

Now, I am a 39-year-old with four children.

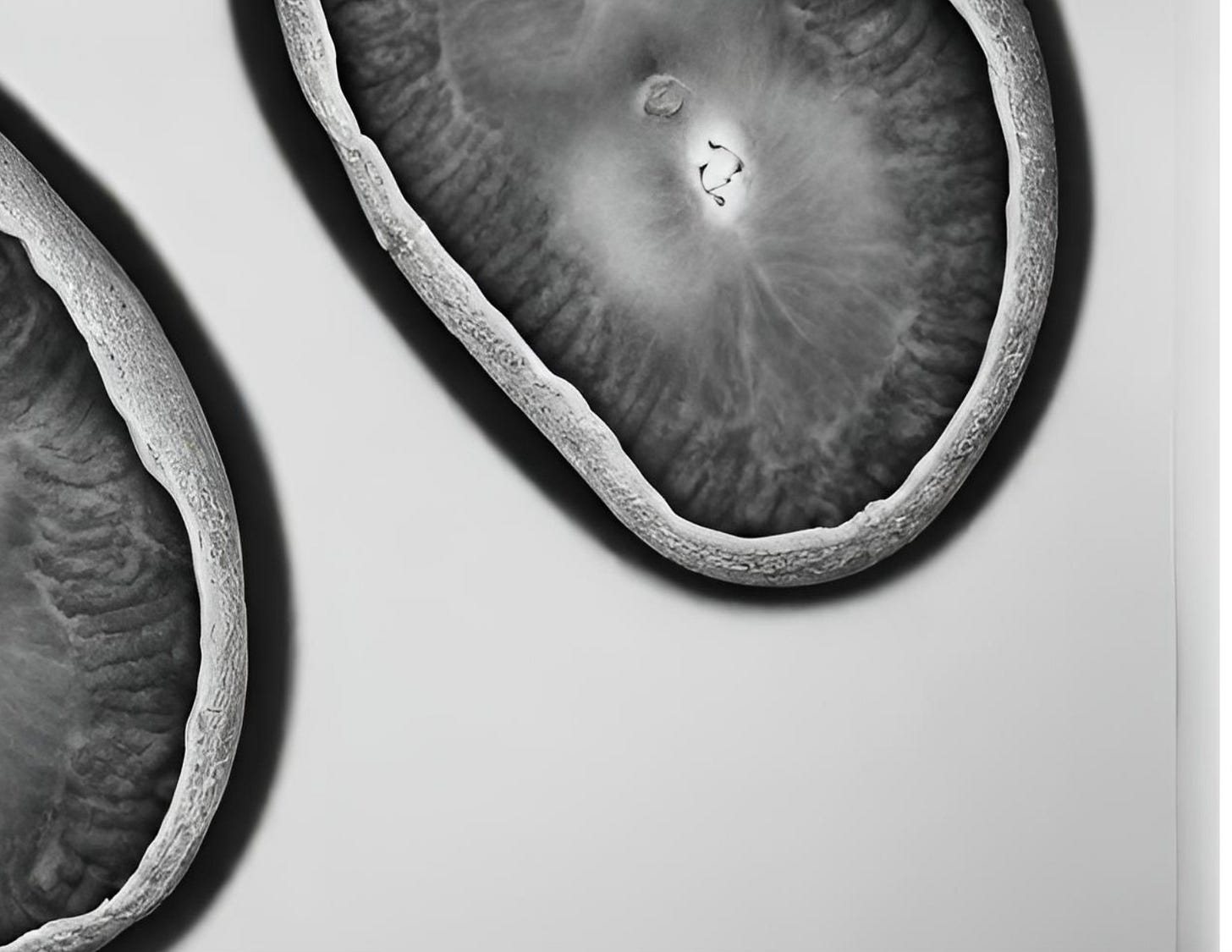

But once, I was a 28-year-old in a thin, starchy gown waiting in an operating room. I wore hospital-issued, fuzzy green socks, and my teeth chattered, but not from the cold. I was waiting to see my future children. When our two embryos were thawed, the doctor would bring me a grainy black-and-white photo of them. Within the hour, they’d be transferred to my body.

But that’s not what happened. When the doctor approached, he was shaking his head. He said a vial of our embryos “had shattered.” He said two “were lost.”

I still don’t know if the vial shattered on impact with warm air, or if it was knocked carelessly against a countertop, or if our embryos were dropped. I don’t know if the lab tech was on his phone, or in a fight with his girlfriend, or stayed up too late watching reality television and skipped his Americano.

I know that two embryos on their way to me never made it. I know that, if that hadn’t happened, at least one of my children would be a different child. I know accidents happen in the IVF process, and I know it can be devastating, as it was for the couples who originally brought the Alabama lawsuit. I know that they wanted to do something to make the pain of a horrible situation go away. I know, from very real experience, that the patients waiting on those cycles are waiting in agony.

I can’t deliver meals to all their houses. I can’t get their hopes and dreams back on the calendar.

My only offering is to choose route two, the one where I admit that the problem is a hard one. To the patients whose embryos were destroyed, to the patients whose cycles were stopped, to the doctors trying to figure out how to proceed, and to the judges, I can at least offer my humility.

It may sound strange, but I think of choosing curiosity as a sacrifice. Curiosity is humility—it begins with “I don’t know.” And humility costs something. I can pay a tiny personal price (time, energy, discomfort, the loss of anchor) in exchange for a little bit of truth, truth that makes its way back into the world. Like moving a single grain of sand on the proverbial beach.

Especially post-covid, the cultural kneejerk is to polarize and politicize. We hear about the Alabama ruling and instantly form an opinion. We pick a side. We plant a flag. Maybe we tweet about it. The time between question and answer is so, so brief.

Sure, some people are in positions that require them to come to finite conclusions: judges, patients, politicians. Rulings must be made. Policies must be decided. Lines must be drawn.

When we need to draw conclusions, we can get there by two different routes. One sacrifices nuance for efficiency. The other tolerates discomfort so it can get closer to truth. (Compassion is just the byproduct.)

On the embryo issue, I was forced into conclusions. I have them, and I could probably argue them in court. It took me ten years.

But not everyone has to have an opinion on this. Sometimes, we can just glance at the precalculus textbook and say, wow, not for me, no thank you.

In this case, we can imagine the hundreds of thousands of IVF stories that might complicate our opinion. We can imagine how our opinion might change if it were happening to us, or to our children, or to our neighbor. And we can adopt a kind of active uncertainty.

I love a song by Iris DeMint that I first heard on the show The Leftovers. Her voice is so weird and wonderful that you really have to listen to appreciate it.

Everybody is wondering what and where they all came from

Everybody is worrying 'bout

Where they're gonna go when the whole thing's done

But no one knows for certain and so it's all the same to me

I think I'll just let the mystery be

I think a lot about the 28-year-old in the green socks. I think about the relief I would have felt if someone had sat beside me on that operating table and said, “This isn’t a problem to solve. This is a mystery.”

I would’ve loved to hear, “I’m not sure what choices I’d make in your shoes socks.”

Or, “It’s okay to not know.”

That’s what I want to give people now: space. That, I’m realizing, is why I write this newsletter. I want to help expand the area between Question and Answer, sometimes infinitely. I want, if you ever find yourself wearing fuzzy green socks, to write you a permission slip.

I want it to say: Breathe.

And: Let the mystery be.

I finally got around to reading this, Lindsey. YES, YES, YES. Please do keep expanding the space between question and answer. Society needs this nuance.

thoughtful as ever, Lindsey. Sending ❤