I spend time with an astonishing array of people every week: pious mothers in minivans, boundary-pushing artists, angsty high schoolers, sweaty bowhunters, nerdy academics, trauma survivors, uber-progressive literary folks (who would, by the way, write that as folx), Christians and atheists and everything in between. I have friends in rural southern towns and friends in Seattle and Boston. I hang out with lots of gay people, lots of sports fans, lots of rich people, and lots of people barely hanging on.

In a single day I often switch from a conversation in which I coolly acknowledge a trans person’s new pronouns to a conversation about the best recipe for beef stroganoff. One minute I’m talking about Magna Tiles, the next I’m parsing the latest episode of Succession. You are as likely to find me dishing on RuPaul’s Drag Race with a student as debating Biblical exegesis.

Every group represents something I love. Being connected to lots of groups makes life rich and fascinating, and I wouldn’t want it any other way.

This kind of diversity necessitates shifts in my behavior, my vocabulary, and even my mannerisms. I speak different languages depending on which moment of my day I’m living—whether I’m teaching or picking up my kid from preschool, at the gym or reviewing work with an editor. (This was exemplified when a male student called my name in class last week and I accidentally responded, as I do to my children, “Yes lovebug?” Sometimes I don’t shift fast enough.)

We all do this kind of code switching, and mostly it is born of empathy—a desire to meet people where they are. I remember being ten years old and noticing the way my dad altered his voice while talking to the man who had just changed his oil—his twang was suddenly accentuated, his sentences slower, his jokes bawdier. I knew intuitively that he changed the way he showed up in the world to make the other guy feel more comfortable.

But code switching also takes a tremendous amount of energy, something I haven’t had much of lately.

For years my social media presence was sparse and carefully curated: I posted only things I knew everyone—all the way from my deceased grandfather to the dean of my school to the woman I met who lives under a bridge downtown—would approve. I thought about people I used to know and people I hadn’t yet met. About half the people I love flat-out disagree with the other half on at least one major issue, so I tiptoed through social media, terrified to offend, hurt feelings, or invite judgement. The only things that passed my Mega Venn Diagram Test were clever, quick, and cute. On the internet, the ol’ Thanksgiving rules applied: no politics, no religion, no feelings.

I spent 90% of my time with my husband and kids, but I didn’t post many pictures of them because of all the time I spent wishing I could get pregnant. A photo of a cute baby face wasn’t worth hurting anyone.

Sarcasm, cussing, and hyperbole are my official love languages, but I mostly managed to hide this from my more polite friends.

I lived in fear of my tenth-grade history teacher, who would definitely disapprove of my politics.

A close family member said he doesn’t understand why people “air their dirty laundry” on Instagram. So despite how much I value authenticity, I was quiet about everything hard and wrong in my life.

Like you, I could write that list forever.

Many of us who surround ourselves with diverse groups manage to move between them without a hitch—and without all our groups ever ending up in the same room. If my Slate-reading friends ever ended up in the same room as my Federalist-reading friends, well, I would not like to stay in that room.

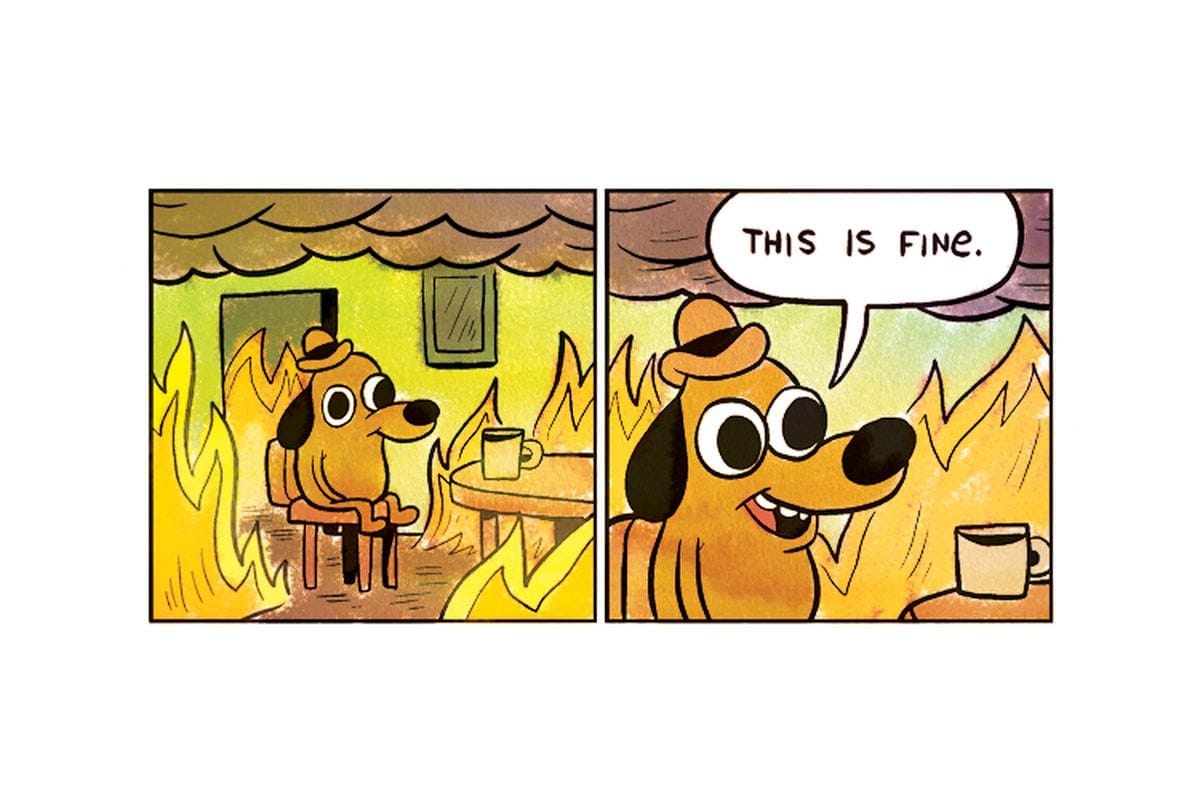

But online? Well, the internet is like ONE BIG ROOM.

Like the Eternal Surprise Party from Hell.

All of this is why, when literary agents told me I needed to “have an online presence” before I could publish my book, I balked. Reading other people’s social media tends to shrivel my soul, and posting my own “content” was like walking unarmored onto a minefield. You mean I could piss off everyone I know at the same time?! Um, no thank you.

If I was going to show up online (which included publishing my writing), I had two choices: I could either pick a homogeneous group and dig my heels in, guaranteeing unadulterated approval from at least a small sector of the population. (See: the first 25 years of my life.)

Or I could be honest about who I am. I could stand in that one big room, facing all the conversations and disagreements. I could tell the truth about what I believe, knowing that every person I know would be somewhere between mildly and deeply disappointed.

[Part Two is here]