At 33, I gave myself a goal: Before I turned 35, I would write a book.

I’d noodled with the idea for years, but I was ready to make it happen. To encourage my goal, my sister sent me this quote from Amy Poehler’s memoir:

Remember, the talking about the thing isn’t the thing. Doing the thing is the thing.

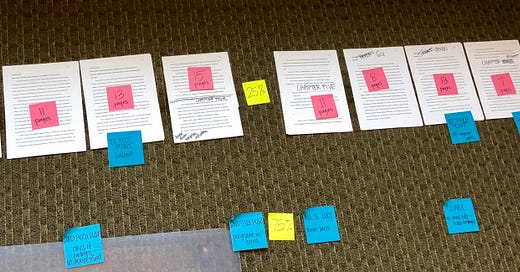

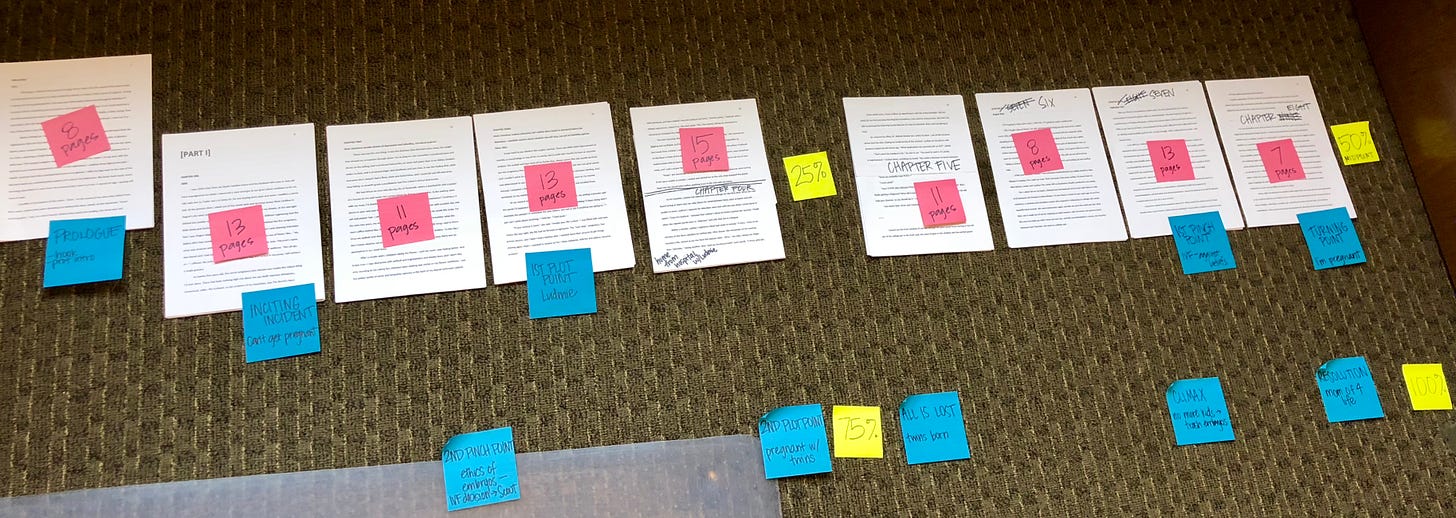

Doing the thing is the thing. For almost two years, I wrote during my kids’ naps and while they were at preschool. I pored over old journals and medical records and photographs. I snuck away to hotels, where I bolted the door and wrote for 14 hours straight sustained only by dark chocolate and vending machine Diet Cokes. I stayed up late printing pages and rearranging chapters on the floor of my husband’s office. I tagged scenes for revision with post-its. I sent myself hundreds of emails that consisted of a single sentence I needed to work into the manuscript.

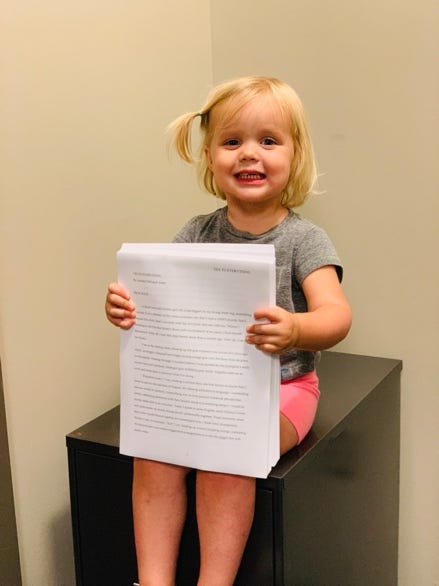

And I did it. A few weeks before my 35th birthday, I finished writing a memoir. Not only that—I had done it during some of the most demanding years of my life. I had worked very, very hard. Like most first-timers, I assumed the most difficult part was behind me.

Now I am 38, and the book is in the same place I left it at 35: in a folder on my computer.

I’m pretty sure if I’d known what was to come after the book was written, I would’ve been too discouraged to begin. I couldn’t have known I’d spend years after the manuscript was complete educating myself about the publishing industry (which is, very much, an unromantic, insular, capitalist enterprise that has almost nothing to do with art-making), rewriting 40 drafts of a query letter and proposal, making spreadsheets of literary agents, and selling my soul (and my data) to “build a platform.” I couldn’t have known a pandemic was around the corner and that I’d manage my kids’ early school years on the desktop computer in our living room, teaching my children to count fake coins and build models of space shuttles out of discarded cans and water bottles. I couldn’t have known the world would grow darker, the publishing industry would be turned inside-out, and I would rearrange my life around a new reality. I couldn’t have known—and if I had, I might not have started.

One thing about me: I do not settle. This is both a character flaw and a superpower, depending on the day. I had ideas about who I wanted to publish the book and which agents I wanted to work with. And on those things, I haven’t budged.

Which means I’ve spent the last few years waiting.

Which is funny, because the book I wrote in hotel beds and in the notes app of my phone and at midnight—it’s largely about waiting. It is about working very hard for many years only to find life had screeched to a halt for reasons entirely out of my control. I had done everything right for 25 years, and then I couldn’t have a baby. Waiting made me sad and terrified, yes, but underneath all that? Waiting made me angry. It seemed like a thing I shouldn’t have to do.

Until just this week, I missed the obvious connection. How had I spent years writing a book on waiting only to find myself shocked, when all the hard work was “over,” by more waiting?

If we’re lucky, the first quarter of life teaches us little about waiting. In our youth, life advances at a steady clip: one homework assignment to the next, one soccer game to the next, one cafeteria lunch to the next. Elementary school to middle school to high school to college to first jobs. One thing builds on the thing before it, so quickly we have no time to consider the length of life (very short) or whether we are doing anything we actually want to do or were made to do with that short life. We just… go.

Waiting belongs to the domain of adulthood.

I didn’t grow up when I got married or got a dog or bought a house; I grew up when life stalled for a moment, and for the first time, I had to wait. Which is to say, I moved forward on the inside only when life slowed down on the outside.

Sue Monk Kidd calls waiting a “crucible of spiritual formation.” A crucible melts a formerly solid material. I wrote a book about waiting because I had experienced that to be true. While I waited (and waited, and waited), my understanding of the world—and my place in it—melted. When something melts, its shape is permanently altered.

And yet. No matter how many times it happens to us (because who would ever choose it?), waiting is never not a surprise. All day every day we move and rush and push ahead, and nothing about the way the 21st-century operates teaches us how to wait. We communicate instantly (and constantly), order gifts and groceries that arrive on our doorsteps, and watch television without commercial breaks. And, understandably, we forget that no matter how many apps we download or lines we skip, waiting is inevitable.

Waiting is, by its nature, an indeterminate thing. When I longed for children, I remember thinking hundreds of times, “If I only knew how this turned out, I could wait as long as I needed to wait.” If I knew when or where or how the waiting would end, I could trust it. But that’s not how waiting works.

This time around, while waiting for my book to exist in the real world, I do not feel the oppressive urgency I felt before. Sure, the stakes are infinitely lower. If I never sell my book or publish another essay or write another thing, my life will still be full of things I love (like those kids I waited for).

But also, I’ve learned some things. The last thirteen years have overflowed with things I could not control. The years have been marked by waiting. I can see now how waiting for kids made me a better mother, and every day I’ve waited for this book to land in the world, it has become a better book. Even if it is never published, the act of writing the book (telling that one story the truest way I knew how) irrevocably changed my life.

Waiting doesn’t make me so angry anymore, because the anger was premised on an entitlement that I have (largely, hopefully) abandoned. I appreciate now that most growth happens just underneath the surface, during the long stretches when we aren’t certain we’ll get the thing we want in the end. This is perhaps the ultimate challenge to modernity: embracing the wait in a world that tells us never to slow down. Embracing the wait might mean endlessly stirring a pot of stovetop risotto or answering text messages only during specified windows or never exceeding the speed limit. These are small ways we might train ourselves in patience.

In his phenomenal book Four Thousand Weeks, Oliver Burkeman distinguishes between “choosing curiosity (wondering what might happen next) over worry (hoping that a specific certain thing might happen, and fearing it might not).” Modern life prizes active certainty and leaves so little space for dormant curiosity and wonder.

Of course, we don’t always get what we wait for. I don’t want to minimize the pain of long waiting, which I have walked through myself and with dear friends. More than once, I have seen it almost break people. So much is hard about waiting that it is important to have a reminder of what good can come of it. W.H. Vanstone wrote a slim little book called The Stature of Waiting that got me through some dark months. He writes, “to man as he waits, the world discloses the power of meaning—discloses itself in its heights and depths, as wonder and terror, as blessing and threat.”

On good days, I can replace impatience with curiosity. For six month stretches at a time, I have been able to forget entirely about the book (and all the accompanying backend nonsense). I feel no panic, no rush. When we aren’t afraid of waiting, we don’t have to rush into suboptimal “solutions” just to end the discomfort. We can thrill to unnamed—even unimagined—possibility. We can play the long game.

There’s a beautiful song by Brandi Carlile, Lucie Silvas, and Joy Oladokun called “We Don’t Know We’re Living” that gives me that pain in my throat every time I hear it. The lyrics are nothing without the melody, so please click here and listen to it. If you won’t, though, here’s a snippet.

I took a trip but I was not on a vacation

I sat face to face with my love but I didn’t see him

Staring out at the Grand Canyon

Oh but I was just so busy planning

The places I’d go

We race out the door of our youth

And wave back to our mothers

We take on the world

And stop taking their telephone calls

We see them again every Christmas

Till there’s not another

Oh, I wish I had known

Birds don’t know that they’re singing

Fish don’t know that they’re swimming

No one knows the beginning

We don’t know that we’re living

“Doing the thing is the thing, yes.” But waiting for the thing is also the thing.

It’s all the thing.

I know it’s corny, all of these things I’m saying. It’s been said (better) a million times. But that doesn’t make it any less true: the living doesn’t happen after the waiting is over. The waiting is the living.

I can relate to this in multiple ways. As someone who experienced the no-woman's-land of secondary infertility, which felt like endless waiting for something that ultimately never happened, and also for someone who writes, waiting has been part of my life's fabric as well. (Not that it isn't in every life.) And the bit about curiosity -- amazing how much curiosity can cure, isn't it?

I don't know that anyone says it better, Lindsey. You keep writing like this, and you won't have to wait for an agent or a publisher. They will find you. Wishing you and your family a Merry Christmas!