We are... queso people?

Considering Libby Epstein, covid revisionism, and the reality of trade-offs.

In both the book and TV adaptation of Fleishman Is in Trouble, Libby Epstein is a 40ish-year-old former journalist who quit writing after her kids were born. She doesn’t regret the choice to stay home; it’s not that. It’s just that, as it sinks in that her life is half over, she begins to feel the weight of who else she might have become. Rather inconveniently, she begins to remember her other self.

For a New Yorker, moving to New Jersey is the ultimate metaphor. Libby has done just that: settled in the suburbs, effectively cutting ties to both her pre-parent identity and her creative ambitions. The metaphor is of death—the death of cool, the death of youth, the death of opportunity. In one of my all-time favorite moments of television, Libby accompanies her family to a backyard bbq (in suburban New Jersey), where the full impact of her choices hits her. She locks eyes with her (kind, patient) husband holding the tray of cheese dip he’s generously contributed to the gathering. Baffled and a bit disgusted, she spits out, “Is this who we’ve become? Are we queso people now?”

I love this line. When I’m at the school fundraiser or pumping gas into my giant SUV or herding four kids down the aisles of Target, I often think to myself,

Are we queso people now?

Like, is the sum of our family ambition a Friday night cookout with a clamshell of Publix chocolate chip cookies and a bunch of grubby kids running around on a square-shaped plot of grass? Is this all there is?

Maybe it’s hard to sympathize with a woman who grieves the loss of one great life trajectory (an illustrious career in journalism) for a different, also-great life trajectory (as a married, financially secure stay-at-home-mom). One response to the character of Libby might be: Boo-hoo.

Wandering around New York City one morning, Libby narrates, “I always returned to the museum of my youth, trying to find the last place I’d seen myself.”

Perhaps she’s a bit self-involved. Perhaps unmoored. For sure, she’s taking it out on all the wrong people.

But that whisper of grief? I get it.

Since my twins started kindergarten last year, I’ve debated (out loud, internally, at night, in the car, in dreams, with friends, alone) whether to go back to work full-time.

I tried to go back to teaching a couple of years ago, and it was just shy of disastrous. It’s hard to know, now, how much of the struggle was related to covid-times, but two working parents with no childcare and four young kids who can’t so much as approach the school entrance with a runny nose makes for virtually nonstop logistical problems. It’s doable, of course, but our family didn’t have the proper architecture to hold it all up that year.

Still, I feel the presence of my other, professionally ambitious self like a puppy at my heels. I want to let her off her leash.

One day in the car, I asked my kids how they’d feel about me getting a full-time job. They are not, of course, the decision-makers here, but I was curious. At first it was a chorus of nos from the backseats, shouted for emphasis. But then they started brainstorming awesome babysitters (who would probably let them eat all the after-school Cheez-its they wanted) and decided they didn’t actually care so much.

Such is parenting—you lay awake every night worrying about them, you cry when they cry, you stash your paychecks in 529s… and, in the end, their analysis of you comes down to the availability of Cheez-its.

Honestly, I like arguing with my kids about Cheez-its. I want to be a part-time work-from-home mom and a full-time working mom. I want to wear sherpa slippers in the carpool line and be a woman who has a reason to wear heels. I want to do both things the best they could possibly be done, ever.

In Fleishman, Libby isn’t supposed to admit that she is a little bit sad about what she gave up. I sense this in real life—it’s shameful to acknowledge the very concept of trade-offs. Like we’ve made a sleazy back alley bargain, we aren’t supposed to confess there was a thing to give up in the first place, much less that we might miss it.

Why are trade-offs so uncomfortable? Is it because acknowledging them requires acknowledging a fundamental-but-unpleasant principle of the universe? When you choose something, you do not choose another thing. Therefore, loss is baked in to the pie.

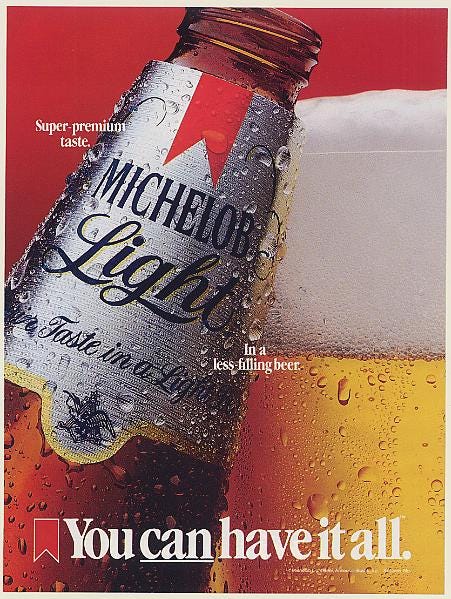

It’s the reason we line entire aisles of Staples with an absurd rainbow of Post-It note options. An abundance of choices fools us into thinking we don’t have to make choices at all.

I don’t think Libby is a brat for wondering what her life would have looked like if she’d stayed the (professional) course. It’s not that Libby thinks she should have it all.

But I think she was set up to believe she could. I think she was set up to believe that being all the versions of herself (Sheryl Sandberg-style) was not only going to be possible but... easy. Like picking out Post-It notes.

In an ideal universe, I would slip silently and effortlessly between two or three people. I’d lead panels and travel and do research—then be home in time to pick up my kids, who would never even know I was gone. I’d zip identities on and off like skin.

It doesn’t work that way.

And I don’t think Libby is necessarily angry to realize that she has permanently traded one thing for another. I think she’s just… surprised.

On a 2023 episode of the Ezra Klein podcast, epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina considers our country’s response to covid, months after the masks came off. She argues that this moment, while we are not in the middle of a pandemic, is the time to take advantage of hindsight, to analyze what we did well and poorly.

It turns out, the episode is as much about the stories we tell ourselves as it is about the virus. At times Jetelina sounds less like an epidemiologist and more like a social psychologist.

When she talks about America’s handling of the pandemic, she laments that the problem was never a lack of resources (as in many countries) but a breakdown in public communication and trust. We had everything we needed… except the skills to think through our options.

We needed to weigh individual imperatives versus public good. We needed to factor in short-term suffering for long-term benefits. We needed to consider correlation versus causation.

We needed to consider cost.

And at that, we failed completely.

“There’s a lack of nuanced discussion around trade-offs today,” says Jetelina.

As the world’s richest, highest-tech culture, we aren’t trained in compromise. For those of us raised on abundance and instant gratification, the mere suggestion of inconvenience, not to mention true loss, incites terror. Which incites rage.

We do not limit ourselves. We do not give things up. We cede neither ground nor points. We are Americans. If anyone can have it all, it’s us.

That’s America’s brand promise.

It’s just… not true.

The math of public policy operates by the same principle as the math of my own life. One choice precludes another.

We’re all making bargains, all the time.

If I want guaranteed safety, I cannot have adventure.

If I want predictability, I cannot have the thrill of spontaneity.

If I want a perfectly clean house, I cannot raise wildly creative kids.

I trade what I do for what I am not able to do.

I think the character of Libby Epstein wishes someone had told her that before she hit 40. The advertisements are lying to you. Sheryl Sandberg is lying to you. You cannot have it all. You have to make some choices.

Loss is part of the gig. Grief is part of it too.

I have 40 Amazon boxes broken down in my garage right now. I recently watched 4 uninterrupted hours of The Great British Baking Show. I am reading 7 different books. I am working on 13 writers’ manuscripts. I own 15 jackets and 32 colors of Olive and June nail polish. My shopping habits are, at the moment, unhinged. I fritter away my hours. I mostly live under the illusion that I can have all the resources, all the stuff, all the time, all the knowledge... and that I need not make concessions. Life is a Staples, and I have a credit card.

Sacrifice is such an old-fashioned word. Compromise is downright disloyal. Trade-offs are out; world domination is in.

Did you know that Sheryl Sandberg, the author of Lean In, publicly amended her position on women in the workplace? Two years after her famous book came out, Sandberg’s husband died. After living as a single mother, Sandberg admitted she “did not get it” before. It was harder than she imagined to succeed at work while also managing a home.

She said, “I have never met a woman, or man, who stated emphatically, ‘Yes, I have it all.’ Because no matter what any of us has—and how grateful we are for what we have—no one has it all.”

Disgruntled Libby might be healthier than most of us. She’s—clumsily—trying to have some kind of conversation with herself about trade-offs. She’s trying to work through the fact that, because she is now queso people, she is not a woman with distinguished bylines.

Here’s Libby’s narration in the show: “How could you be this far along in life and still so unsettled? How could you know so much and still be this baffled by it all?”

Amen.

In the covid podcast, Klein muses about our society-wide experience. “We are captive not just to partisanship but to certain kinds of wishful thinking and coping mechanisms, so we’re not seeing what we went through clearly enough to learn from it or reckon with it.”

Whatever you might say about Libby, she is in it.

Oh, we hate it. We despise the muddling through.

It’s too scary, sometimes, to say the trade-offs out loud. We rely instead on the wishful thinking that tells us “having it all” is just around the next corner. Therefore, compromise and resignation are weaknesses. There’s nothing worse than being only the thing we are, whatever our own version of queso people is.

Maybe it’s against her own will, but at least Libby’s getting honest with herself. Knowing we can’t have it all is a good place to start.

And maybe, like Libby, I get a bit crisis-y on occasion. It’s healthy, I think, to acknowledge what is lost as well as what is gained. To admit to ourselves that it hasn’t gone perfectly as planned.

But mostly, when I am alone in the car wash line and I whisper Are we queso people now?, I make myself laugh. Sometimes out loud.

Yeah. We are queso people, whatever that means. Occasionally I wear heels, and occasionally I deliver important lectures to hundreds of people. But mostly, the suburban backyard bbq is where I landed. It’s not so glamorous, but it’s the one life I am going to get.

And, sorry Libby, but who doesn’t love queso?

Feel this all deeply — I have a toddler, am massively pregnant, about to have two under two and still every day spending hours and hours thinking about my career, how to manage it all, whether or not it’s even manageable!!! I found your substack through your recent Motherwell essay which I loved as well. Thanks for your generous openness in your writing

Great post. Relavent, relatable, deep, and personal. Like a good sermon manuscript! I want to know the answer to this problem. Is it compromise and acceptance?