Read Part One first.

Caring as I do about words, I sometimes try to resuscitate words that suffer in public consciousness from negative connotations—words like conflict and failure.

A word that comes up frequently in my own writing is tension.

Tension is such a great word. I wanted to put it in the newsletter title, but I can think of few things people want to avoid more than tension. Unpleasant things spring to mind: a tension headache, tension in the room, sexual tension, hypertension, ornery Aunt Maude.

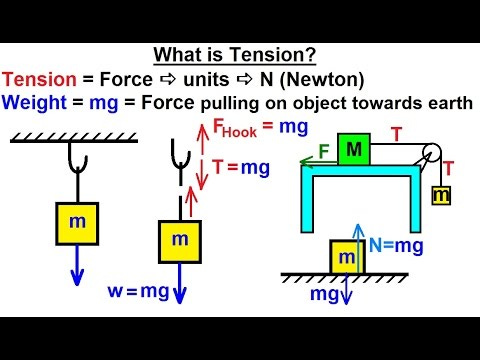

But the word originated in science, and in that discipline, it is connotation-free. Tension is a neutral physical reality. Listen to how boring this definition is: an action-reaction pair of forces acting at each end of the said elements.

But let’s pretend for a moment that, like Michael Scott, we need tension explained to us like we’re five.

A science website for kids defines tension as “a force that stretches something.” The website goes on to say, “Materials are only useful if they can withstand forces… In a tensile force, atoms are pulled apart and springs are stretched until they break, which is when the material fails.” And now we are in the realm of metaphor, and my brain is back online.

Something I say in conversations a lot is “hold the tension.” I say it to my creative writing students who are trying to discern whether a character is good or bad. What happens, I ask, if you rightly assume that she is neither good nor bad? Can you hold the tension between those two extremes? Without a doubt, complex characters make more interesting stories. So holding the tension is a practice that gets us closer to reality.

I say “hold the tension” to my kids, who try to navigate questions like whether it’s more important to be fair or merciful. I say it when they have been hurt by a friend they thought loved them. I even say it to my husband about our own relationship, like yes, okay, I did screw that thing up, but let’s hold the tension and remember how awesome I am at this other thing?! Mostly I say it to myself; I have a list on my phone of extremes between which I actively practice holding tension.

Here are a few: strength and weakness, change and stability, suffering and rest, doubt and certainty, dependence and autonomy, fairness and grace.

On any given day, the internet proffers articles praising one element of these pairs while decrying the other. Here is, say, an article aimed at tired mothers validating rest. Here is an article aimed at Christians validating certainty. Here is one aimed at a girl in an unhappy relationship validating autonomy, and it has some inane, clickbait title like “Is Your Lover Trying to Control You?”

What these articles do is dichotomize our brains. They make complicated things (i.e. communities, institutions, relationships) black-and-white. Your lover is controlling you—dependence is bad! They turn our brains into “materials that are not useful because they cannot withstand force.”

(Nevermind that if you do a little digging, you’ll find different articles on different days in the same publications praising the opposite things: “Do You Need to Give Up Control in Your Relationship?” Today, autonomy is bad!)

Some mothers advocate total self-sacrifice: soak up every moment, enjoy them while you can. Others tout self-care: you are not your children, treat yourself.

Some say respect authority; others say challenge power.

Some self-help gurus advocate complete open-mindedness; others preach the importance of banishing doubt.

I am convinced of this:

Wisdom resides in the complicated, messy, blurry space between two things. Wisdom comes when, for prolonged periods, we intentionally hold tension. Once we plant our flag in the soil of unadulterated conviction, we miss recognizing what exists in the space between two versions of knowing.

WATCH THIS:

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie on the danger of a single story.