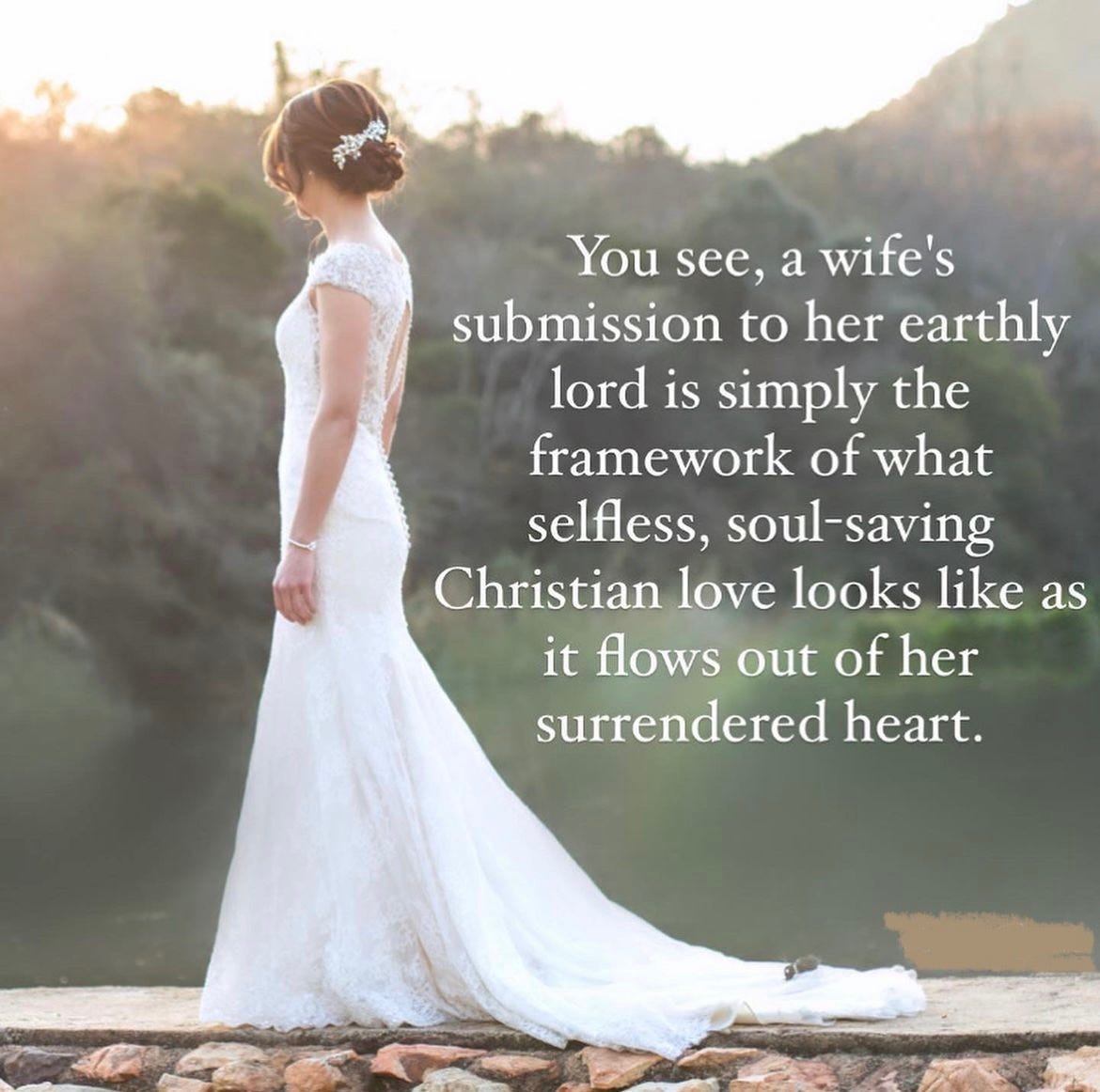

Because my brother-in-law is a (loveable) sadist, he gets a real kick out of sending me Instagram accounts he knows will make me throw my phone against a wall. One such account is called The Homemaker’s Manifesto, on which a Christian woman argues that wives ought to take pride in their role as homemakers, ensuring a clean and peaceful environment for their husbands when they return from their work outside the home.

I mean, I don’t happen to agree that I need to vacuum the rug and shush the children before my husband crosses the threshold, but okay. If it works for the homemaker wife and the professional husband, whom am I to disagree? Vacuum away.

What’s underneath her supposed advocacy, though, is a more sinister message. Her primary argument is that feminism (in all forms) is dangerous.

I offer here a couple direct quotations:

“Feminism is the philosophical manifestation of the Curse of Eve, as recorded in Genesis 3.”

“Feminism has never ‘just’ been about ‘equal rights’… They take the right to vote, own property, and serve in public office and conflate it with abortion access, radical social theory, and the disruption of traditional sexual norms and ethics.”

I have questions.

Who are “they”? And where, pray tell, are the feminists wrenching sourdough starter from the flour-dusted hands of American homemakers? Which “radical social theory” do I, as a feminist, supposedly endorse? Why is the “Curse of Eve” capitalized?

MAKE IT MAKE SENSE.

I don’t care if women are homemakers and want to dust their bookshelves and make elaborate homemade meals and homeschool their children. Because of course I don’t care! Of course women can provide incredible value to their families by performing these actions, and women who aren’t forced to work other jobs are lucky to take plenty of pride in homemaking. I love homemaking, especially the squishy babies part.

But.

Feminism isn’t one thing. The ideology itself has varied over centuries and across cultures, and feminists are as diverse as any other large group of human beings.

But.

This Instagrammer utilizes as a strawman what she considers the most egregious form of feminism, then builds argument after argument against that misconstrued and exaggerated stand-in.

Even considering all this, it’s not the opinions of this woman that make me crazy. We are all entitled to our own.

It’s the “Manifesto” part.

A manifesto is “a public declaration of policy and aims.” It is “a statement making clear a person or group’s intentions or views in a way that is easy for others to ascertain.”

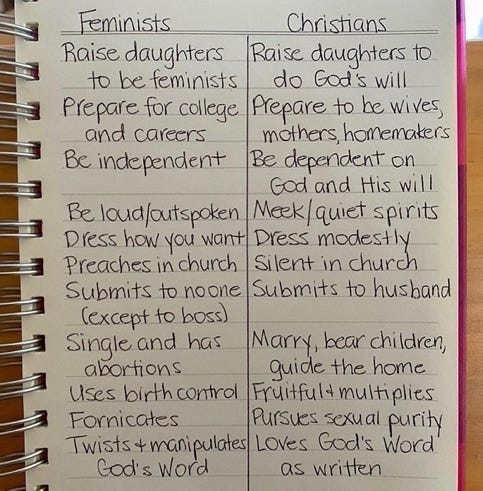

By generalizing and oversimplifying entire movements and positions and geographical regions and historical eras, this woman erases the complex and varied stories of b-i-l-l-i-o-n-s of human beings. In countries other than America, gender equality isn’t about vacuuming and feminism isn’t about abortion. This woman has Canva’d her graphics until they are “easy for others to ascertain,” blending fact + opinion + full-on falsehood and packaging it in a design polished enough to seem reliable. She has written, as she herself calls it, a manifesto.

What’s missing in a manifesto is story.

I don’t mean only fictionalized stories or canonized stories or even bound-into-books stories. I mean the narratives we tell ourselves and others to make sense of things.

The woman behind The Homemaker’s Manifesto has a story to tell that is almost certainly worth hearing. It involves how she came to realize, for her, the pitfalls of feminism.1

A story is something you write about yourself. A manifesto is something you write for someone else. Someone you don’t necessarily know.

And because of this, a manifesto cannot make room for the complexity of the human experience. Anything that is “easy to ascertain” runs the risk of reduction. By attempting to speak for all women, our manifesto-writer effectively says nothing at all. Instagram lady2 is entitled to her opinions; she just isn’t entitled to mine.

In reality, labels of “Christian” and “feminist” can (and often do!) apply to the same woman. As can the labels “feminist” and “homemaker.” Actually, I have zero desire to make a case for feminism or it’s supposed opposite; rather I am using this account as one of a billion modern examples of the damaging rhetoric used to divide people who should be on the same team.

When we behave as though terms that can (and often do!) coexist are in fact mutually exclusive, we are “writing a manifesto”3 void of nuance, compassion, and the reality of a diverse humanity.

The act of telling a story is personal. Done well, it stakes no claim on others.

In fact, it makes space for other stories, some of which will align with and others which will diverge from (or contradict) our own.

A manifesto is you should; a story is I did.

A manifesto is you should be; a story is I am.

A manifesto declares; a story asks.

A manifesto dispenses; a story exchanges.

A manifesto closes; a story opens.

A manifesto assumes; a story wonders.

A manifesto makes us feel watched.

A story makes us feel seen.

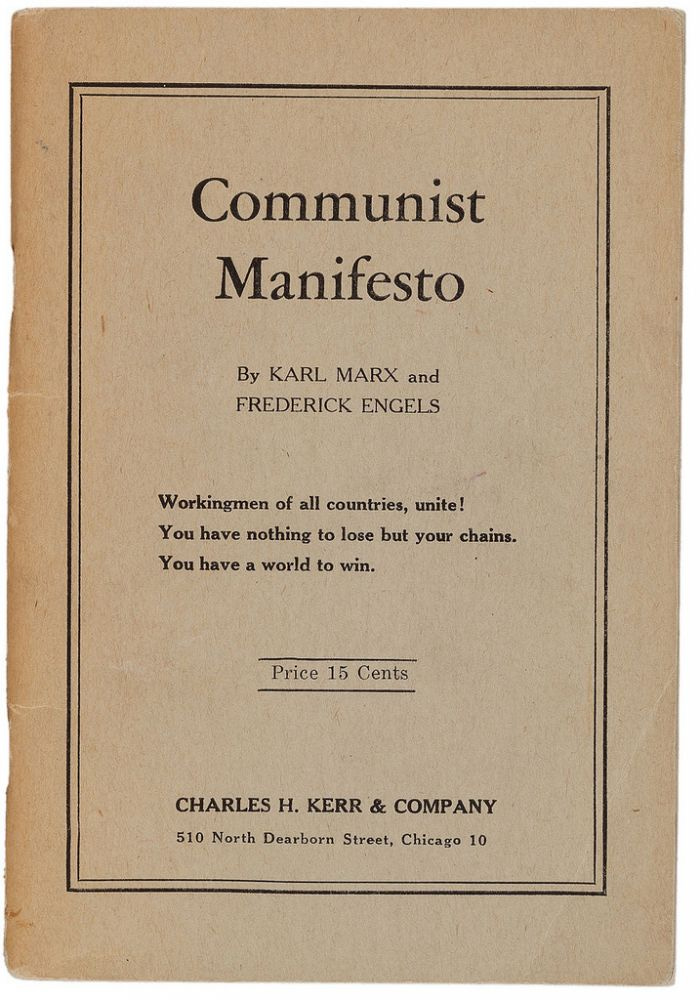

Arguably the most famous manifesto in western civilization is the Communist Manifesto, written in 1848 by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels. In it, the authors state “[t]he history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.” Of course this manifesto is much maligned inside democracies, and I’d have quite a few bones to pick with it myself. (Is some of history attributable to class struggles? OF COURSE IT IS. Should all people participate in a “forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions”? I don’t recommend it at this time.)4

In writing a manifesto instead of telling a story, Marx made himself (a) easy to argue with and (b) easy to exaggerate and (c) easy to condemn. How many documents can claim to have cornered the market on truth—forever? How reliable is a document padlocked against future interpretation? In this way, a manifesto is hubris.

And Lord knows I’m unqualified to tackle the finer points of Marxism here, but I think it’s worth noting that sweeping manifestos attempting to speak for large (or all) populations are often misleading at best and dangerous at worst.5

For a living, I teach stories.

Beautiful ones, difficult ones, heart-stopping ones, mundane ones.

When they turn the final page of an assigned story, rarely is a student’s reaction to argue with it.

What we teach in English classrooms, instead, is the art of “wondering about it.” What is it trying to say? What does it fail to say? And how, practically, does it do those things?6

One of the many beauties of a carefully told story is that it is impossible to argue with. It simply doesn’t invite argument. It invites speculation, curiosity—even awe.

Another beauty of a good story is that it is both familiar and unfamiliar. It is familiar because, in order to work, all stories must hang from the clothesline of our shared humanity; it is unfamiliar because every story is new—only that writer could have written it (or speaker could have told it) in precisely that way.

All of this means it’s hard for an open-minded person to encounter an honest story and not be changed.

People’s stories—where the familiar (what’s in me) encounters the unfamiliar (what’s in another)—have changed my life more than any other factor. I have, for example, disagreed with people’s politics many times, only to listen to a recounting of that person’s (often unexpected) set of experiences, experiences which make their conclusions logical and reactions warranted. I’ve been put off by other’s offenses against me, only to painstakingly rewrite the story I was telling myself about that person, which then led me to realize that in another, perhaps truer version of that encounter, I was the villain instead of the hero.

Also for a living, I write stories.

A dedication to writing stories, I’ve found, can teach a person an awful lot about living.

Any writer worth her salt writes toward questions, not explanations.

Any writer worth her salt embraces revision (“re / vision”), the practice of seeing the same problem again and again from different angles.

Any writer worth her salt is plagued by a fear she isn’t getting it quite right—and it is the presence of that very uncertainty that makes literature transcendent.

Stories are small and mighty and myriad, whereas manifestos loom large, leaving no space for curiosity or conversation—not to mention flaws, missteps, or mistakes.

Manifestos can’t qualify or complicate—it’s against their very nature to do so. How would a political platform or denominational doctrine or school handbook make room for nuance?

We are all, I think, being manifesto-ed to death.

“We [substitute any powerful group here] believe this, and so should you.”

“We have it figured out, and all you have to do is join up.”

“We have access / knowledge / power not available to you; trust us.”

“Relax. Sign here.”

Manifestos do not allow for dissension. Distinction. Doubt.

I understand our appetite for the manifesto, for the Instagrammer who will tell us what “They” (again, where can I find the Big Bad “They”?) are doing wrong. The Instagrammer who will give us a step-by-step guide to health and wealth and rightness. The world is terrifying in scope, and we long for clarity.

Stories, on the other hand, require our imaginations.

The difference between a manifesto and a story, you might say, is the difference between religion and faith.

Between assenting to ideas and embodying them.

Between prescriptive and descriptive.

Between this-or-that and a third way.

Here’s how I describe what’s happening here, at Between Two Things:

Between Two Things is the space where I work out my obsession with a simple-but-complicated idea: binary thinking gets us into real trouble, and it is the job of the artist to hold a middle way. As a writer, I wanted to create a space for complex thinking, where questions are more important than answers and people can be wrong without being cancelled.

I never, ever set out to write a manifesto. It is possible that, after many years of constant affirmation in the same direction (a closed in-group), my writing could calcify and codify. I could begin to believe all the questions had been answered, and the stories I tell could turn into manifestos I tack on telephone poles.

If that day comes—and I hope you’ll tell me—I should cap my pen.

P.S.

Here is a stunning poetic “manifesto” by Wendell Berry, which is (like this post) actually an anti-manifesto.

Ironically, one occasional pitfall of feminism is the idea that all women who are homemakers are selling themselves short. That particular brand of feminism arguably erases nuance the same way this Christian woman’s account does.

I realize this moniker sounds snarky but I am actually just so tired of calling her “this woman” and I’m committed to not sharing her real name.

As I’m using this term in the space of this post only, which is more ideological than literal.

I do think that, in drawing attention to class struggles, this document initiated much-needed dialogue around equity.

This is especially true in the hands of someone as ill-equipped as our Instagrammer to tackle mid-19th-century Germany. Here’s an ironic tidbit from our righteous homemaker arguing against Marx, our righteous socialist: “’Women’s liberation’ is simply another form of Marxism that seeks to ‘liberate’ women from the family unit.”

Did you know you can get whole degrees in “wondering about it”? Begin your search in the Humanities department of any accredited university.

Your posts always makes me throw my phone down in my lap even after just the first paragraph, as if a bomb went off in my mind and I’m overwhelmed by the profound truth you write. I love you! You’re such a kindred soul. You are what the world needs!!

I love how the list-maker says Feminists are all single and get abortions🤦♀️. I think there are statistics that most, or at least many, people who get abortions already have at least one child, and many are married. And they all have stories. Stories will set you free! P.S. I wrote about an amazing book about abortion rights earlier this year and want to tell everyone about it. https://open.substack.com/pub/louisejulig/p/abortion-without-apology?r=29kh6&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post