Assembling the Elephant

Confessing Our Blindness Helps Us to See

When I began “interrogating my cognitive framework” circa 2008, I didn’t have words like “cognitive framework” to describe what I was doing. I didn’t have words like “moral matrix” or “deconstruction” or “heuristics.”

The only language I could have come up with at the time to describe what I was doing? Heretical. Lonely. Dangerous.

Considering my reliance on language for making sense of things, it is unsurprising that, in the intervening years, I have searched tirelessly for words that could gesture toward what I would now call (something like) a knowledge renewal or expansion. In the next post I’ll talk a little about the events that triggered this, but ever since those events, I have become increasingly interested in thinking about thinking (which, if you've spent any time reading Between Two Things or my Instagram, you well know).

I have a clear image of the way my mind operated until I was about 25. When an unfamiliar idea approached, a heavy steel door swung shut just in time to block it. With Truth already in my possession, I had no need for new ideas. Not only that, but contrary ideas threatened my intellectual (and moral) purity, so the steel door was a necessary protection.

Because that door was impenetrable, I didn’t get much out of my college education. Everything I heard was tested against what I already knew, and if those things were misaligned, slam went the door. In this way, my mind was protected from newness… but also from learning.

In 2021, I read several books that helped me see the big picture of cognition. They gave me language and supporting research for a lot of the concepts that, for more than a decade, I had only intuited in a blurry, disjointed way. The most impactful was The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt (after which I read The Coddling of the American Mind, also by Haidt). I read Excellent Sheep by William Deresiewicz and Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. I read Strangers in Their Own Land by Arlie Hochschild and Blind Spot by Mahrazin R. Banaji. I listened to a podcast by Brian McLaren called Learning How to See (and lots of others I can’t remember).1

I took notes in the margins, highlighted passages, and stayed up late with a book light and pen. During this period, my husband and I sometimes joked that I was studying for an exam I’d never take. (This reminds me of the saying that being a writer means voluntarily giving yourself homework every day for the rest of your life.)

I also read a book that year called The Great Mental Models. It is not a particularly scholarly book (Epistomology for Dummies?), but it simplified some concepts I wanted to wrap my head around, and in that regard, it’s really good. (I’m borrowing from it for much of this post.)

One argument the book makes is that American education poorly equips us for real-world decision-making. We graduate with a shallow knowledge of “sine” and “cosine” (wow, that trigonometry flashback hit harder than a wave of morning sickness) but with a dearth of true decision-making wisdom that can be applied across disciplines and in practical contexts. “Not having,” says the author, “the ability to shift perspective by applying knowledge from multiple disciplines makes us vulnerable.” (I’d add “and angry… and self-righteous… and divisive.”)

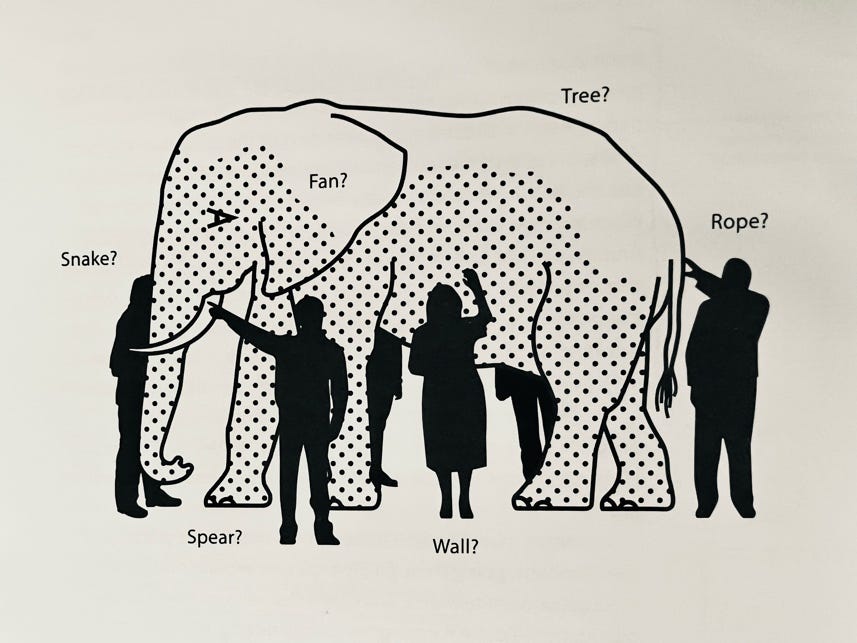

A valuable analogy for the way we think (also referenced in this book) is that of blind people approaching a strange animal they don’t realize is an elephant.

No one knows the object’s full shape.

The first blind person touches the trunk and announces the object is like a snake. The second touches an ear and claims the object is a fan. The third person touches the leg and says the object is a tree trunk. A person with a hand on the elephant’s side thinks he is touching a huge wall, and a person who touches the tail declares the object resembles a rope. Finally a person blindly touches the tusk and decides the thing is hard and smooth like a spear.

“Right now,” says Parrish, “you are only touching one part of the elephant, so you are making all decisions based on your understanding that it’s a wall or a rope, not an animal.”

Okay, so we can’t see the whole elephant. None of us can—least of all me.

But just realizing we can’t see the whole elephant (and, because we are “blind,” never will) goes an awfully long way. When we don’t imagine that we alone2 see and understand the whole elephant, we interact differently with other people. We approach problems differently. We graciously allow for more perspectives and personalities. We invite more people to dine at our proverbial tables, always with the presumption they have something to add that we’re missing.

We stop thinking about how everyone else is blind and instead think about how we are.

How I am.

Yesterday, on the first warm day in what seems like a thousand years, I spread a blanket on the expanse of crunchy, still-brown grass in our front yard.

I didn’t have to tell the kids to come outside; if the blanket is out, so are they. (Also, if I want the kids to join me anywhere, I need merely open a book to read and they will flock to me with questions that have become suddenly urgent.)

With one kid balanced on my back and two lying on either side of me, we started talking about God. (I can’t remember why, but I suspect the unexpected gift of a warm day got us in the mindset.) As we talked, one six-year-old insisted heaven is on Mars; another insisted God has black hair “just like Mom’s brother.” The nine-year-old interrupted to remind the twins that God is neither a man nor in possession of a body, then said “heaven will just be wildness, like with absolutely no machines.” She suggested heaven isn’t a place at all, so we talked about black holes and unseen dimensions and what cosmic mysteries might be hidden from view.

I let them wonder.

I offered no corrections. No answers.

Fifteen years ago, this kind of interaction would have terrified me. To young Lindsey, the entire point of faith was getting things right. That Lindsey would have parented with a constant pit in her stomach, ceaselessly scrolling the Rolodex of her knowledge for correct responses.

I don’t worry about accuracy in that way anymore. I believe it would be a tragedy to offer to my children the leg of an elephant when the animal itself is bigger than I will ever, in my blindness, see.

Long after I should have started dinner, I reluctantly pried the kids off my body to fold the blanket and gather our things, now splayed across the yard. As we groaned our way to sitting positions, we spotted a single blade of green pushing up amidst the expanse of deadness. We (literally) rejoiced, shouting “Spring is coming! Spring is coming!” My children clapped and danced.

Had I become a parent a long time ago, I am certain I would have missed that moment. I would have been too busy crossing out mistakes and recalling Bible verses and making mental lists of all the ways I’d failed to impart accurate information to my children.

I can no longer imagine a God who thinks accuracy matters most.

It’s easier for me to imagine a God who thinks the blade of grass matters most.

You can see how, throughout my life, all this thinking about thinking has been inextricably linked to God. After all, the way we think about anything determines the way we think about God and vice versa (including whether we think about God at all).3

Most people feel the leg of an elephant, are told it’s a tree trunk, and spend the rest of their lives insisting to everyone around them it’s a tree trunk.

If we twist the analogy just a bit, imagine a person feeling the leg of an elephant and getting it right: it IS the leg of an elephant. But then that same person insists that the leg of the elephant is the entire creature.

That’s how I once thought about God. The leg was the whole elephant.

A premise of BTT is that all models are flawed in some way. If someone had figured out politics in a way that perfectly represented reality, we would cease to argue. If someone had figured out parenting in a way that perfectly represented reality, we would just apply the principles across the board and raise universally healthy children. If someone had figured out Christianity or faith in a way that perfectly represented the reality of God, we wouldn’t argue about theology or choose from dozens of denominations cordoned off by their own rightness.

If the perfect model of Reality became apparent to all people across all time, we would just Know. And our decisions would fall outward like dominoes from the indisputable Truth.

Anytime a person attempts to operate inside gray space, people inevitably hurl accusations of “Relativism!”

Relativism tells us that, because truth exists in relation to culture, there are no universal truths.

Subjectivism tells us that, because truth exists in relation to the individual, there are no objective truths.

I get why relativism is scary; no one wants to believe they live in a world where nothing is true. And furthermore, we all instinctively know some things just are.

“This” isn’t that. This (shall we call it elephantism?) doesn’t posit there is no truth; it merely suggests that I/you don’t/can’t know all of it.

It’s not relativism to say you don’t see the whole of truth.

It’s humility.

In The Great Mental Models, Shane Parrish writes,

An engineer will often think in terms of systems. A psychologist will think in terms of incentives. A business person might think in terms of opportunity cost and risk-reward. Through their disciplines, each of these people sees part of the situation, the part of the world that makes sense to them. None of them, however, see the entire situation unless they are thinking in a multidisciplinary way. In short, they have blind spots. Big blind spots. And they’re not aware of their blind spots. There is an old adage that encapsulates this: “To the man with a hammer, everything starts looking like a nail.” Not every problem is a nail.

I’d add to this mono-disciplinary approach the complications of personality, disposition, inherited values, and life experiences. We are who we are, and we see what we see, and we don’t see what we don’t see. It can seem there’s no getting around that.

A bit of a side note: One reason I appreciate the Enneagram (a fluid personality typing system) is that, although it is a flawed model like everything else, it helps us “see” the personality that was before invisible to us. It shows us (and gives us language to describe) a framework we are so accustomed to we don’t even know it’s there (our little slice of perspective in a much larger pie). In so doing, the Enneagram enables us to think critically about the perspective of our personality—and begin to move beyond it as opposed to only within it.

Which is to say, maybe we can, occasionally, get around it.

Every single day, I wonder why I keep writing. I wonder what good it can possibly do in a world facing problems so big we can’t even conceive of them. I wonder why I speak when someone else is always more qualified and thoughtful. I wonder why I don’t just, on the one hand, do something concrete to help the world, or on the other hand, put up my feet and watch more reality television. Who needs stories, and who needs them from me, of all people?

Alain de Botton said, “The chief enemy of good decisions is a lack of sufficient perspectives on a problem.”

If a business person thinks in terms of risk-reward, a writer thinks in terms of story.

This is the only reason I keep writing. Because what stories do is offer new perspectives. I don’t see the whole elephant, but I do see a part of it. So do you. If, from a place of generosity, you offer to the world what you’re good at, and I offer to the world what I’m good at, I think we can get closer to truth than we would alone—or inside our like-minded bubbles.

Frederick Beuchner famously said, “The place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.”

Writing is my deep gladness, and I think the world is hungry for good stories that help explain reality.

I can’t overstate the excitement I now feel when I encounter new ideas. When the steel door swung open, I couldn’t get enough of what began to pour in. I don’t think everything I hear is “correct” or good or true or beautiful. But I do think (maybe with rare exceptions?) even the person whose ideas seem the most flawed or outlandish sees some injustice or weakness in the world I’m missing. Or can offer a creative solution I couldn’t have invented.

If we just admit we are blind, I think together we can assemble tusk and tail and, maybe, envision something closer to the truth of the animal we are touching.

If you are a big reader, I have a tip I love: Every time I read a book, I write my name and the month and year I’m reading it. I like being able to look back and see which books were influencing me simultaneously. So I could, technically, hunt down the other books I read during this time, but I’d have to pull them all off the shelves and check the front cover.

or, “our in-group alone”

I don’t mind (in fact, I like it very much) if you are here and atheist. Or just uncomfortable thinking about God. As I hope I’m communicating, I think you have much to offer me and see much that I don’t.

How do we know reality? How do we know we’re touching an elephant? If we’re all somewhat blind, how can we know anything?

I was listening to Rainn Wilson on BFNP today, and I’m wondering how much spiritual insight Rainn, who’s not Christian, can bring to people with a Christian perspective. I heard a quote by Thomas Aquinas recently that “theology is the queen of the sciences”, but this assumes truth is knowable.

Rainn’s Baha’i faith rejects the core distinctives of Christianity. For us to incorporate the opinions of those who reject our opinions will lead to some type of Unitarianism that can’t believe in objective truth.

I can’t get my mind wrapped around the idea that reality is largely unknowable.

I just really appreciate your line of thinking! I would love to hear your thoughts on the fear of leaving, (or transcending but also including), one’s tribe, whether it’s, religious, conservative, liberal or any kind of tribe, when one’s insights or values no longer fit within the parameters of one’s tribe.