During the US Open a couple of weeks ago, a climate protester (wearing a t-shirt that read “End Fossil Fuels”) glued his feet to the floor of Arthur Ashe stadium. The tennis semi-finals were interrupted and, ultimately, 49 minutes delayed.

3.4 million people watched. 3.4 million viewers were inconvenienced. Their nachos grew cold, their beers grew warm, their eyelids grew heavy, their anticipation of a victory stalled. Their bedtimes were pushed back. They were forced to scroll. They were forced to wait.

I watched with some friends, and there were grumbles among us. I’ll admit that it was probably my utter lack of interest in tennis that kept me from being annoyed. I was more fascinated by the protesters than by the match. (Someone did what? Why praytell?)

Eventually, the match resumed, and tennis icon Coco Gauff went on to win and reach her first US open final.

If anyone had the right to be furious it was Gauff. She’d trained nearly her entirely life for a moment that might have been ruined by a nutjob1 with a tube of Superglue.

But Gauff wasn’t angry. From The Guardian:

She said she held no animosity to the protesters, although she did think their timing could have been better.

“It was done in a peaceful way, so I can’t get too mad at it,” Gauff said. “Obviously I don’t want it to happen when I’m winning up 6-4 1-0, and I wanted the momentum to keep going.

But hey, if that’s what they felt they needed to do to get their voices heard, I can’t really get upset at it.”

I know little league dads who’d get angrier than this at a cat crossing the outfield.

It’s Spirit Week at the local middle schools, so send up a prayer for all the mothers in your life. This morning my 6th-grade daughter dressed in a mash-up of historically inaccurate 70s garb. Her teacher had dispensed advice: Straighten your hair. Wear bell bottoms. Deck yourself out in peace signs and flowers.

As I painted a peace sign and flower on each side of her face, I asked her if she had any idea why those symbols were popular in the 1970s. (Nope.)

She was my captive; I had a paintbrush (and, apparently, her popularity) in my hands, so I dove in. Many people, I explained, opposed America’s involvement in the Vietnam War, and wearing peace signs was a way to peacefully protest.2 Even the flowers (and the phrase “flower power”) originated as a symbol of non-violence resisting more nefarious forms of power and violence. Eventually, war resistance was absorbed into the popular culture; people covered themselves in flowers without knowing why (not unlike the yin-yang choker I wore every day of 8th grade).

My eleven-year-old daughter was only (and I mean only) concerned with what the rest of the 6th grade would or would not be wearing for Spirit Day. I’m not even sure she put down the book she was reading at breakfast. But I didn’t care if she retained information; I wasn’t trying to educate her.

I was reminding her to wonder about things. I was reminding her to pay attention to people with convictions.

Because I’m a huge advocate for curiosity. Curiosity for President.

When an entire generation of college kids makes peace their whole vibe, I am intrigued. What was it about the Vietnam War that bothered young people enough to extinguish their joints and make posters?

And when the End-Fossil-Fuels-Guy chooses a tennis match to take a (permanent? lol) stand, I want to know things.

I wonder: How could this issue matter so much to a person?

Which makes me wonder: What cause would I be willing to glue my feet to the floor for?

Which makes me wonder: What might I have in common with this person?

And, ultimately: What am I missing? What does he know that I don’t?

(Not to mention: What kind of glue? How will they get him out of there? When they do, will he still have footprints?)

If the answer to any of these questions turns out to be meh or nothing or who cares or whatever or ew or yikes, I have spent only a little energy, and even that energy is not “lost.” Merely the act of wondering, I want to teach my daughter, has real consequences. Imagination matters. Curiosity is how we put ourselves in another person’s shoes or, as the case may be, another person’s sore feet.

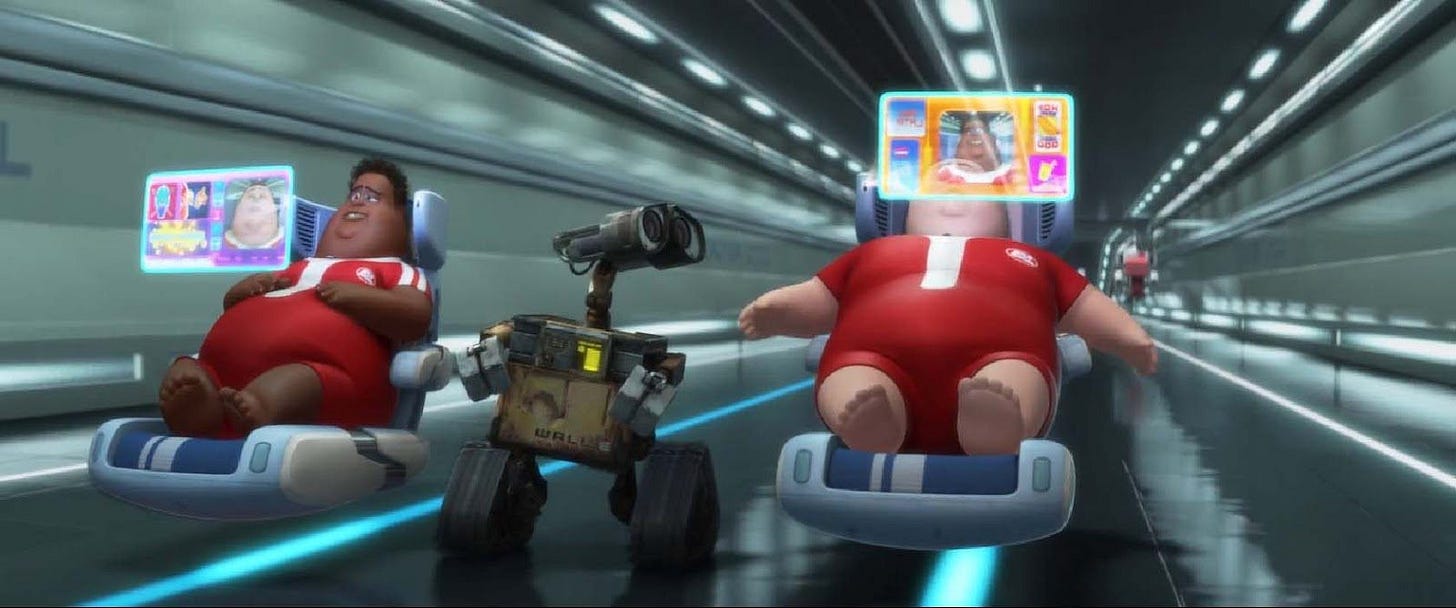

The only reason asking questions could be considered a waste of time is if only one value measure is used: the measure of efficiency. Efficiency has its place, but too often it convinces us that waiting is death and that asking questions is weakness. It convinces us to shunt interruptions, noticing little about the world other than our nachos growing cold.

We all know people with closed worldviews. Closed worldviews thrive inside tribes that depend on thickly-drawn boundaries. In this country, ideological tribes show up not just as hate and activist groups but also as socially-sanctioned religious communities and political parties. Even if these people are curious about familiar things (say, another person in their tribe), they aren’t curious about unfamiliar things. They don’t care about alternate worldviews.

Why would they? Theirs are fixed.

Ideas that approach the black circles they’ve drawn around themselves bounce right off.

I used to be this person, worse than most. In so many ways, I still am. Plenty of topics raise my hackles and my blood pressure. New ideas can feel as threatening to modern Americans as cave bears were a couple thousand years ago. In the face of threat, like all of us, I jettison curiosity.

Which is one reason protest is so tricky. If it’s significant enough to protest, it’s Significant (with a capital S). Issues that attract protesters are the very ones bound to tempt us toward volatility. When someone protests, both the agitators and the observers are provoked. That’s the nature of the beast.

We’re no longer protesting Vietnam, but wars are always happening. There’s a war for our attention, our money, our bodies. Our books. Our weapons. And yes, a war is waging over fossil fuels and conservation and climate change, which is itself really a war over ideologies.

Take climate:

On the one side, you have either visionaries willing to take an unselfish, long view of the future—or you have unhinged, hypersensitive radicals.

On the other side, you have either cool-headed, progress-oriented entrepreneurs—or you have anti-science, consumption-obsessed money-grubbing capitalists.

You get to decide. Who are the Good Guys? Who are the Bad Guys?3

We’re all making choices about how we see the people on both sides of every debate, and those choices are the result of a thousand choices we’ve made about how to see the world and our place in it. And those choices are the result of values we’ve inherited and acquired and honed and codified. Often I’m not even conscious why I side with one tribe over the other. It feels like instinct: run from the bear.

Only questions break the gridlock.4

Back to the tennis match. When I said out loud that the protest made me, at the very least, interested to hear what the protester had to say, someone responded, “It makes me uninterested.”

Okay. We’re all guilty of shutting down when someone protests our beliefs or interrupts our agenda. There’s so much emotion around it.

But can’t we all, if pressed, can think of something we’d be willing to glue our feet to the floor for? If there is nothing we would protest, then there is nothing we love.

A society that protests nothing is a society that loves nothing.

A world with protesters might unnerve or inconvenience us, but a world without them should terrify us. That’s a world in which conformity is not just encouraged but mandated.

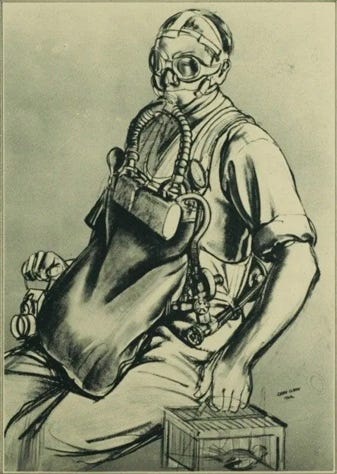

People have always done crappy things, and other people have always been around to protest.

That doesn’t mean protesters are always virtuous. Sometimes we humans wrongly direct our energies toward inconsequential issues. Sometimes we fight back against good things out of misplaced fear or anger. Sometimes we place our bets on bad predictions. Sometimes we use resistance as an excuse for violence.

Sometimes we get it wrong. Our inclinations toward protest aren’t always trustworthy.

But sometimes, thank goodness, we get it right. And (usually only in retrospect) we are grateful to the Rosa Parkses and the Malalas and the John Lewises who saw things we didn’t, or stood up when we were too afraid (or, these days, distracted).

After the fact, we celebrate the canaries sacrificed in the coal mines of our toxic ideas.

Looking back at history’s nightmares, we all want to believe we would’ve been the one who caused a ruckus. We would’ve protested, revolted, screamed injustice from the rooftops—and we would have done it in the face of derision and scorn and eye rolls.

Statistically, we are almost guaranteed not to be that person.

Statistically, we are almost guaranteed to the be the folks inside our houses, carrying on with our distractions and indulgences while other people fight the war—and other people protest the war.

We Lived Happily During the War

Ilya Kaminsky

And when they bombed other people’s houses, we

protested

but not enough, we opposed them but not

enough. I was

in my bed, around my bed America

was falling: invisible house by invisible house by invisible house.

I took a chair outside and watched the sun.

In the sixth month

of a disastrous reign in the house of money

in the street of money in the city of money in the country of money,

our great country of money, we (forgive us)

lived happily during the war.

Statically, we are almost guaranteed to be the ones, when it’s all said and done, begging for forgiveness.

But why protest during the tennis match?

The football game?

The inauguration?

Isn’t it just… inconsiderate?

Well, yeah. In order to effect change, protests must disrupt. Disruption is the only weapon against complacency.

Protesters, as Anne Waldman writes, make the ground rumble under your feet:

“I’m coming up out of the tomb, Men of War / Just when you thought you had me down, in place, hidden. / I’m coming up now. / Can you feel the ground rumble under your feet? / It’s breaking apart, it’s turning over, it’s pushing up. / It’s thrusting into your point of view, your private property.”

It’s thrusting into your television screen, your sporting event.

Not all protests are created equal. Some protests are more like tantrums; others are more like attacks. Destruction never encourages questions. Much could be written about the blurry lines between noble protest and destructive dissent.

And maintaining a curious stance is doubly hard because we don’t just stopper curiosity when we disagree with a protester. Uncritical agreement can be just as dangerous as automatic dismissal. We have to be curious about what we believe as well as what we don’t.

Do protests always—or even usually—“work”? Probably not. But none of us is harmed by a reminder to look up and pay attention.

Good protests cause people to ask questions, even if that question is just Huh?!

Or, What do you mean? What are you trying to say? Why are you wasting my time?

Even, What is wrong with you?

Because at the heart of What is wrong with you? is another question.

What is wrong?

And the answer to that question is what every protester is trying to say:

Let me show you.

Regardless of your views on climate change and greenhouse gas emissions, it’s hard for me not to respect a guy willing to take a stand.5

That’s what protesters do. They force us to look away from our entertainment and away from our self-righteousness toward what is wrong.

I, for one, was a little bit inspired.

I think I’ll start by protesting Spirit Week.

This is a rhetorical device meant to emphasize the hypothetical, not how I really feel about Glue Guy.

The peace sign was originally made from symbols for N and D and stood for Nuclear Disarmament.

Whoever the Good Guys are, I bet you’re one of them! (And, same.)

I have 14 more glue-foot puns where that came from.

I’m so curious about the link in footnote 4 but it’s not working for me!

Yes! for paying attention to the convicted! Yes, for being curious! Tara Mohr (author of Playing Big) has said that fear has less room to waft around when we let curiosity lead (paraphrasing mine). A great big Hell Yes! to protesting Spirit Week. Deviations from the standard course of school preparations are just mean to parents. I appreciate that you're bringing up protest versus outrage. It's easy to do the latter, many times a day. Takes more effort, snacks, childcare and a parking plan to do the former. The attorney general in my state was just acquitted of what seems like pretty obvious crimes (multiple, very sad whistle blowers from his own team testified) that included literal trashcan fire. I only know he was acquitted because I get the paper newspaper. No one outside my home has mentioned it to me. The whole thing makes me so disappointed. That it happened, that no one seems to care, that I feel so demoralized about it to work up much outrage, much less protest. // Thanks for this post.