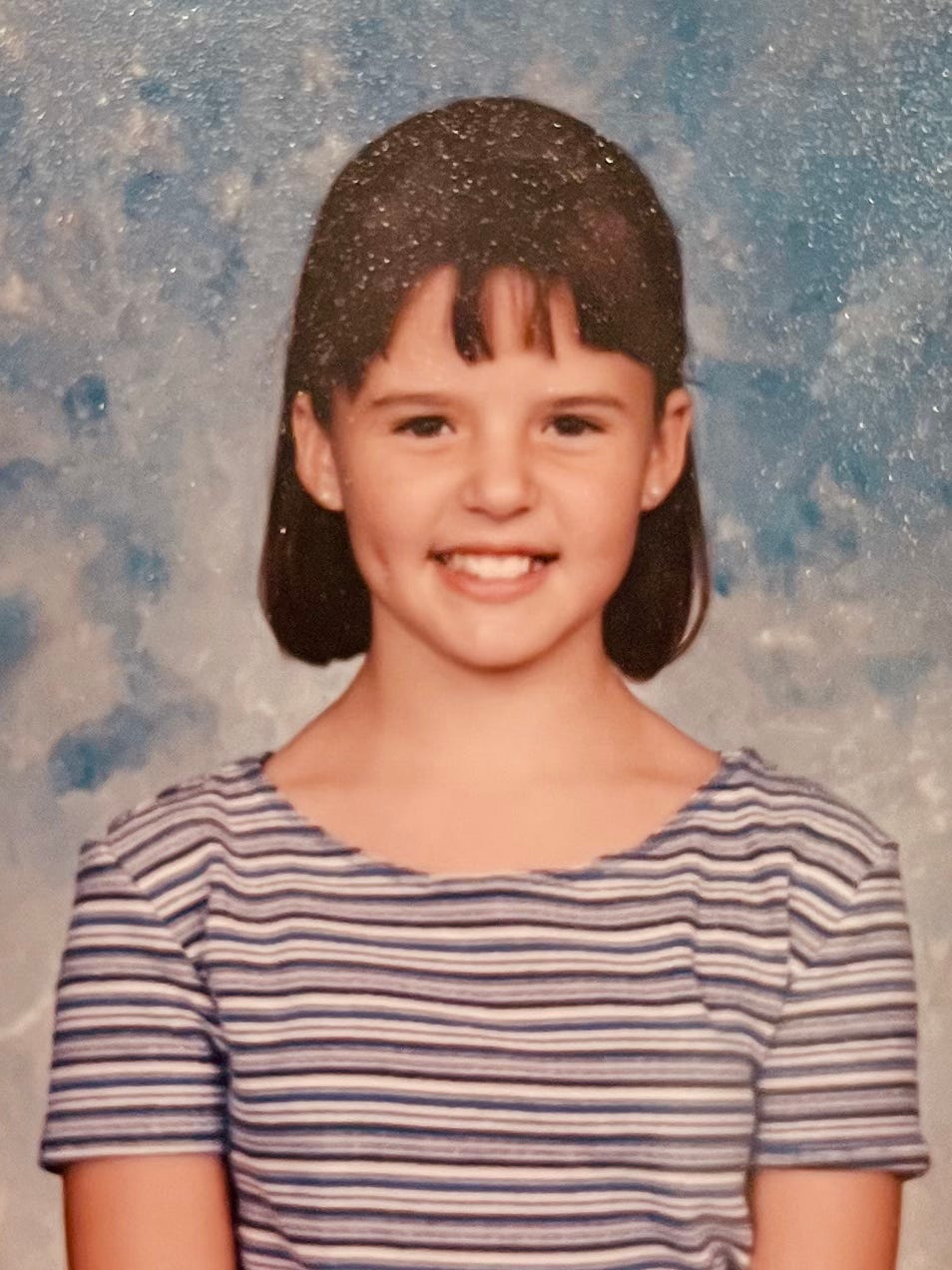

In fourth grade, I won first place in the school “oratorical contest,” a speech competition sponsored by the local Optimist Club. To enter, students had to pick a topic, write a speech, memorize it, and deliver it (charismatically) behind a podium. Speechmaking and I were a natural fit, probably because I relished a room full of people giving me their undivided attention and then clapping.

I went on to win the district competition but lost at state. If I remember correctly, my speech was about the importance of a positive attitude, and the winner’s speech was about the importance of reducing the national deficit.1

The desire to fit in (and puberty) came for me young. The following year, in fifth grade, I was too embarrassed to sign up for the oratorical contest. Despite my pride in the set of gold spray-painted trophies on my bookshelf, I wasn’t going near any elective contests, academic or otherwise.

I was, suddenly, “cool.” And contests were, suddenly, uncool.

My mother was devastated when I backed out of the speech competition—and as a parent now myself, I can understand why. I’d found this thing I loved and was good at, and I was letting some arbitrary definition of coolness (a standard set by a bunch of 11-year-olds whose actual taste was inversely correlated to their own confidence in it) keep me from doing it. As a mom, you have a deep sense of your kid’s unique giftedness, and it is acutely painful to watch them squander it on the altar of belonging.

Of course, I was unmoved by my mother’s disappointment. Probably, her reaction confirmed that my abstention was the right move, socially speaking. But it wasn’t just my mom. At youth group one night, one of my friend’s parents approached me, her lips set in a harsh thin line. “If you don’t use it,” she said ominously, her finger inches from my nose, “you lose it. It’s as simple as that.”

It’s been 30 years since Ms. Miller wagged her bony finger at me in the church fellowship hall. I must have known I was being an idiot—why else would I remember?

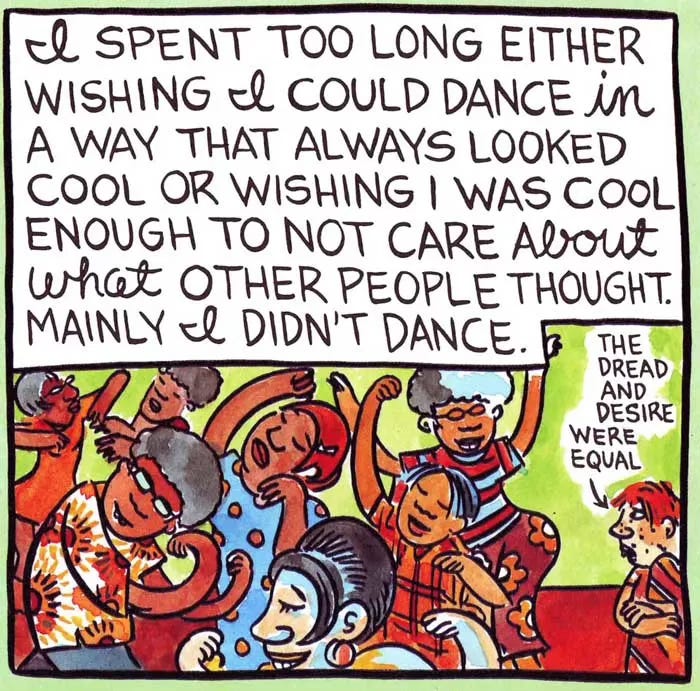

Cool-chasing would define the rest of my middle and high school years. I was afraid to indulge in my friends’ edgy escapades, so my brand of “coolness” centered on avoidance of anything that wasn’t unanimously peer-approved. As a result adolescence was, for me, a systematic soul hollowing. I became a below-average soccer midfielder but abandoned the novels I’d breathed like air until middle school. I fawned over pimply boys with feathered upper lips but wrote poems only in secret. I don’t remember picking up a paintbrush or blackening my fingers with charcoal sticks from sixth grade until I was a freshman in college. (In college I once again sat in front of a drawing easel, tempted to weep with joy.)

Time after time, I rejected what I loved, instead fostering ironic detachment.

Inside my hormone-addled heart and prefrontal-cortex-less brain, I thought I understood:

Allowing things to matter to you made you vulnerable.

Love made you awkward.

Trying made you foolish.

I spent last week painting faces for my oldest daughter’s middle school musical. In total, it amounted to about 20 hours in a backstage dressing room with sixth, seventh, and eighth graders. Today’s theater kids discuss social issues as confidently as if they invented thinking itself, dropping gender theory vocabulary like we dropped your-mama jokes. They sincerely believe they’re the generation to discover both Queen and Britney Spears, and they pontificate on the rule of Ho Chi Minh with the self-assurance of a Vietnam scholar tenured at Yale University.

Just the act of listening to them for a week was hilarious and exhausting and amazing. I could practically smell the hormones—or was that the Cucumber Melon body spray I once spritzed inside my middle school locker?!

I had been equal parts proud and astonished when, despite her absolute terror, my daughter auditioned for the musical. The role she was given suited her perfectly, and I spent months of rehearsals living vicariously through her, pretending to have been the girl-who-tried.

After opening night, within minutes of meeting her backstage, my daughter told me she’d spotted a few of her classmates in the third row laughing and pointing at her and her friends onstage. When she said this, it was like the world went still. I ought to have empathized with my daughter, but I didn’t. I had not, at 11, been the girl on the stage. I had been the girl in the third row.

By sixth grade (the age my daughter is now), I had perfected the eye roll. Before long, my whole life was an eye roll.

That night, my heart ached for the eye rollers. Is there anything—anything?—more miserable than hating things? Like a parasite exploiting its host, contempt claims all the energy available to it.

There’s a reason contests, like school musicals, felt so uncool to me as an eleven-year-old girl. They required a kind of raw vulnerability—a will I/won’t I roll-of-the-dice. They required exposure, opening the door to public failure.

Contempt, I thought, was safer.

These days, I worry life isn’t long enough for me to do all the things I love. I love books, writing, learning about literally everything. I love painting; gosh I love it. I love drawing. I love cooking. I love word games,2 growing tomatoes, taking notes only I will ever read, creating sets and costumes and doing elaborate stage makeup. I love making up puppet shows with my kids, covering the driveway in sidewalk chalk, clumsily explaining the world to seven-year-olds and eavesdropping on middle school conversations. I love gin gimlets and homegrown zinnias and heavy blankets. I love, I love, I love.

If I avoid doing the dishes, it’s not because I resent putting away spoons. It’s because, as I place every one, I think of things I would rather be doing. Time is short, and the world is big, and I want it all.

I was in my late twenties or early thirties before I actively decided to love things again. To begin with, I signed up to lead a southern lit book club at our local bookstore. I’d studied southern lit in grad school and taught it at a university. But this was different; for once, I wasn’t going to talk about books for a grade or because someone was paying me. I was going to talk about books because, well, I love books.

I remember a similar moment, this one in eleventh grade. Maybe I understood that I was leaving high school behind, that my classmates’ opinions would no longer matter to me in another year or two. Maybe I just saw time running out. Whatever the reason, I auditioned for the high school play. I still remember the fear, the inexperience, the sense of stupidity I felt reading a script on that stage, being told to “Project! ProJECT!”

Since I’d spent the past four or five years scoffing in their direction, it took me a while to win over the drama kids. One of them, Amber, confessed outright that she’d spent years hating me. (We were good friends by the time of her admission.) Since I’d made a point of shirking every theater-related event for years, I was offered only a bit part in the play, as a nurse named, of all things, Wilhelmina. My character’s name, hairstyle, costume, and story line were all deeply uncool. I had to fake-kiss a boy who smelled like onions. It’s maybe the most fun I remember having in high school.

The stakes are higher now. In an essay called “The Midlife Unraveling” (worth a read), the inimitable Brene Brown writes this:

Just in case you think you can blow off the universe the way you did when you were in your twenties and she whispered, “Pay attention,” or when you were in your early thirties and she whispered, “Slow down,” I assure you that she’s much more dogged in midlife. When I tried to ignore her, she made herself very clear: “There are consequences for squandering your gifts. There are penalties for leaving big pieces of your life unlived. You’re halfway to dead. Get a move on.”

If I could go back to middle school, I would audition for the school play. I would enter the poetry contests. I would write that speech, and I would give the hell out of it. I wasted years and opportunities refusing to love what I loved. I wish I could have them back.

But I’m grateful I lost only a handful of years to dry disinterest, numbed out on social approval. “Choosing to numb the midlife unraveling,” says Brown, “is choosing to numb the rest of your life.”

I can’t stop thinking about the girls in the third row. I want to hug them. I want to shake them. I want to whisper in their ears. I want to scream at them. You don’t have as long as you think you do, I want to say. I want to be like that woman at church, the one whose gravelly voice scolded me like a terrifying middle-aged lady-prophet. You don’t get it back.

But I want those girls, unlike me, to listen.

When you are too afraid to love things, when you have become convinced that detachment is cool and coolness is the pinnacle of existence, you’ll travel great distances to undermine and annihilate others’ joy in what they love. When you have shut off the tap of your own passions, it is too painful to watch someone else love.

It’s instinct; you don’t want anyone to have what you can’t allow yourself.

I know.

Contempt isn’t safer, not really. Trying to live “above it all” results in a life that is just that. Always the cold observer, never the lunatic, the fool, the lover. “Above it all” is the seat in the third row.

It’s one thing to let middle school pass you by. Who doesn’t, in one way or another, squander those sweet, bitter years?

It’s another thing to miss your life.

I think we were made to do it—whatever our it is—all the way. I want to die with soil and stage makeup beneath my fingernails, charcoal on my palms, notebook pages crinkled with the earned words of a life that was lived. I’d rather have you roll your eyes at me (at that sentence!) than sit beside you in judgment, cool once again.

This is what I told my daughter, by the way. “I have been the girl laughing and pointing from the third row,” I said. “I’d rather be the fool onstage.”3

It was a pre-internet world, and I had access to a limited number of facts.

Seeking group for highly competitive text thread re: Connections scores.

“It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again... who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly.” ―Teddy Roosevelt

Hi Lindsey! I saw this mug and immediately thought of you. You simply MUST have it! I’d love to gift it to you as a way of thanking you for sharing your beautiful writing, book recs, musings and curiosities. Please reach out to me via email at cammie@me.com if you’d like. (I bought your car when you found out you were pregnant with twins and have never forgotten your precious family!)

https://www.bando.com/products/hot-stuff-ceramic-mug-book-person?_pos=1&_sid=521997104&_ss=r&sscid=51k8_f07a&utm_source=shareasale&utm_medium=affiliate&utm_campaign=!!affiliate&ID!!&utm_term=!!banner&ID!!

I just want to say that I could not breathe as I read your words about "being cool." I thought it was just me who had squandered so many precious years in an effort to hide the person I thought was so uncool and certainly most unacceptable. It happened to me in dance class when I was 11 and I went underground in an instant, staying hidden through adolescence and a good chunk of my adult life. I am now 71 years old and just last year went back to dance. I am intentionally and consciously trying to live every single precious moment.

Thank you so much for reminding me of how it was and who I became and, most importantly, of the freedom to choose that I now truly cherish. It is NEVER too late.