For my last birthday in June, my husband bought me a 4-session watercolor class at the local arts center. (Which is to say, I sent my husband an email that said “birthday present please” and pasted in a link, and he clicked it.)

I’ve played around with watercolors for years but never taken it seriously until that summer class. It was my first visual arts class since college, when at eighteen I took drawing (but asked to opt out of the nude model class because I was afraid the model would be a man and I was one-hundred-percent a fundamentalist. My drawing teacher, who before that incident had said I “had promise,” despised me after that.)1

Anyway, I hadn’t really learned anything about visual art since becoming an adult, and I sopped up that watercolor class like I was a crusty old sponge. Because I kind of am.

On the first day, when our instructor asked if there was anything specific we wanted to learn, I asked if we could try portraits. Portraits are notoriously difficult, and I have never had any luck with them on my own. During our second session, we all painted a photograph of one of the students in the class, taken by the gallery window just moments before. Here’s mine.

To get started, I was mixing up a bunch of shades of brown on my palette when the instructor came around to my table. Leaning over my shoulder, she said, “This is a good skin tone for some areas. Now look here.” She pointed to a place on the woman’s face. “Do you see the green here?”

I remember thinking, Do I see green? Um no. This is a FACE.

While I skeptically squinted, she said, “And see the purple tones here?” She ran her finger down the woman’s jawline.

This lady had lost her mind. Purple and green faces, yeah okay. Can I get a refund?

A few minutes later, she called us up to watch her paint the same photograph. I studied the way her brush flitted with practiced ease across the paper. Using deft strokes, she brought to life the woman’s face using shades of brown and pink and yellow and purple and green. “Here,” she said, her brush moving across the paper, “is where the green of her shirt reflects onto her skin.”

And all the sudden, it clicked. I just saw it.

I saw colors that weren’t there before. A thing that had looked monochrome and simple to me suddenly appeared as complex as it actually was. A palette of brown suddenly became a palette of a dozen, hidden colors.

But, of course, those colors had been there all along.

Last week my kids’ school had some controversy over a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion statement that was introduced. I kept calling the conflict a “kerfuffle” because that word made me feel better about the fear and accusations and vitriol that seemed to erupt overnight in our school community. I’m sitting in a meeting where white people are arguing about brown people in front of brown people. Hahaha, what a kerfuffle!

Truth is, it really shook me up. That incident and some recent controversy at our public library over banned books in South Carolina seemed to deliver to my front doorstep some of the issues I’ve been watching play out on a national scale for the past two years.

This is not a post about skin color or race or politics. This is a post about colors.

It’s about how we can look at a person—or an issue—and think we see all there is to see. And one day, someone leans gently over our shoulder and points, and in an instant, brown becomes green and purple. And you realize brown has always been green—you just missed it.

Or, to use a more familiar metaphor, black-and-white becomes grayscale.

Remember that book you almost certainly read in fifth grade, The Giver?2 In the fictitious world of the book, the whole society has happily “relinquished colors” in favor of uniformity. But as the protagonist Jonas learns new things, asks unaskable questions, and breaks free of fundamentalist thinking, he begins to see glimpses of what he later understands as “color.” In the book, The Giver calls Jonas’ ability to see “Seeing Beyond.”

What’s interesting is that everyone in that society was thrilled with their black-and-white version of the world. They thought it was not just okay but perfect—a utopia finally achieved by way of uniformity.

I could talk about WWII Germany here, but I won’t. This is a post about colors.

Sometimes I wonder why people are so fixated on their own ways of seeing the world. I shouldn’t wonder because I spent 25 years thinking my mind could not, would not be changed. My inflexibility was a point of pride.

I had only lived in Georgia and South Carolina when I went to grad school across the country in Seattle. Within a five-year span, I had a dozen friends and countless conversations I never imagined having. All of them—the people and the conversations—were weird. My life became instantly richer. But it didn’t end there. I started eating foods I avoided before, appreciating new art, reading books I thought were off limits.

Between 25 and 30, my black-and-white world went rainbow.3

This is a post about colors, but it is also about how we see. Last Christmas I read Jonathan Haidt’s book The Righteous Mind, and it provided language for what my intuition had been whispering for years. Seeing the world in black-and-white is an evolutionary strategy. It makes us feel Right.

Feeling Right makes us feel Safe.

Most of the time, we’ll take Safe over Real.

I became a much better painter in class that day. Later at home, I watched a YouTube video about color theory, obsessed with understanding how, for years, I had missed seeing what was right in front of my face.

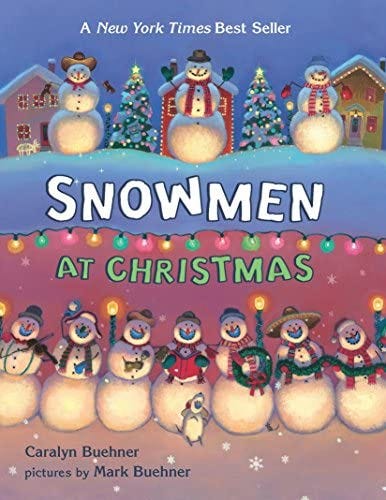

Recently, at a meeting for my kids’ school book fair, I was charged with painting giant snowmen to decorate the library. Glancing at the pages of the book we were imitating (called Snowmen at Christmas), the librarian said she’d order lots of white paint for me to paint the snowmen.

But the snowmen weren’t white, not at all. They were yellow and purple and blue and golden. I would need whole bunch of colors, I told her. Because of that watercolor class, I could something I couldn’t see before.

And that’s when transformation happens—when we learn how to see. Brian McLaren has a phenomenal podcast called just that: Learning How to See. He talks about confirmation bias (we believe what fits in with what we already think), community bias (we believe what our community or “tribe” believes), and complexity bias (we prefer a simple lie to a complicated truth).

We all do this, all the time. It can feel like a matter of survival. But, knowing we are doing it really helps. It reminds us to study things closer, until brown becomes green. Until black-and-white becomes gray.

And, maybe, if you’re really committed to seeing, grayscale becomes rainbow.

And her despising me made me feel even better about myself. Which matters here.

Sadly, the book does not hold up to an adult reading, which I learned a few years ago when I discovered the tiny paperback at my parents’ house. But when I was 10? It blew my mind.

I keep trying to avoid the word “rainbow” because I’m afraid someone will try to think I’m making a point about sexuality I’m not trying to make. But I am equally annoyed that a word like rainbow can’t be used without everyone’s vision, ironically, going black-and-white. And this is a post about colors. So it stays.

Lindsey- this gives me such hope. Please don't ever stop writing. Our world needs your voice.

Wow, you’re good! This really went straight to my heart and mind. I’m in my late 70’s now and have been rethinking all that I accepted as right and true. I’m not playing safe anymore and I like it! Can’t wait to read more from you! ❤️