Welcome to Worth It, a weekly(ish) round-up of the very best of what I’m reading, watching, listening to, and occasionally even cooking. Only the things absolutely worth your valuable minutes.

Everything Sad Is Untrue | Daniel Nayeri

Here’s what I realized when I read this book: I love books with child narrators. I think what I love is the uninhibitedness, the lack of self-consciousness, the reminder of how we might see the world more honestly. (These also happen to be my favorite traits in human adults.)

Everything Sad Is Untrue manages to be charming and even funny despite the heavy subject—a broken, displaced immigrant family. When he flees Iran with his mother and sister, little Khosrou ends up in wildly unfamiliar Oklahoma. And he’s as unfamiliar to midwestern kids as they are to him, resulting in a painful-to-read social dynamic that makes Khosrou the butt of every fifth grade joke (all the more painful because our young narrator sometimes understands this and sometimes misses the joke entirely).

Khosrou is renamed “Daniel” by his mother, though this of course does little to bridge the cultural divide. All he wants are his favorite Iranian candy bars and the father they were forced to leave behind. He weaves the story of his family and homeland in the magnificent Persian tradition—rife with mythology and ancient tales and enchanted digressions. (And also some digressions about poop.)

It turns out, it is all true—this is the author’s actual story. It’s just that, like most true stories, “what happened” is less important than what the story reveals *about* and *to* the people who hear it.

The child perspective is so poignant it might choke you up at points. (But what do I know—I never1 cry about books.) An all-around feel-good memoir.

On Being with Krista Tippett

This is like the OG, the podcast of all podcasts, and it went away for a while, and I grieved, and now it is back, and I can be happy again.

Unlike much of what I listen to and read, this podcast is (and has been for 20 years) relentlessly hopeful and not-at-all self-conscious about its bigness. Which is to say, it is an open-hearted discussion (in an interview format) about life’s grandest questions—but there’s no apology offered for embracing mystery and abstraction, for leaning hard into the search for meaning. No apology is made for setting aside those enticing hits of information we spend our days googling (as though we are amassing a thousand bricks of information with which to build around ourselves fortresses of knowing).

The gracious host Krista Tippett (a hero of mine) eschews information-as-such and instead makes space for deep knowing and deep unknowing. And, in fact, that space is sometimes actual silence, mid-podcast.2

I’ll admit: based on what I’m describing, OnBeing sounds like a podcast for people who live with their heads in the clouds and their fingers in the “om” position. Actually, I know dozens of folks whose feet are firmly planted on the ground (or inside a cubicle) and who nonetheless treat this podcast like weekly soul fuel. It allows those of us with insufficient moral imaginations to borrow one from some of the world’s best thinkers and dreamers.

Side note: If you are a person for whom faith in God has become complicated, this podcast will meet you there. And if you aren’t a person for whom faith has become complicated, be careful—because this podcast might complicate it for you.

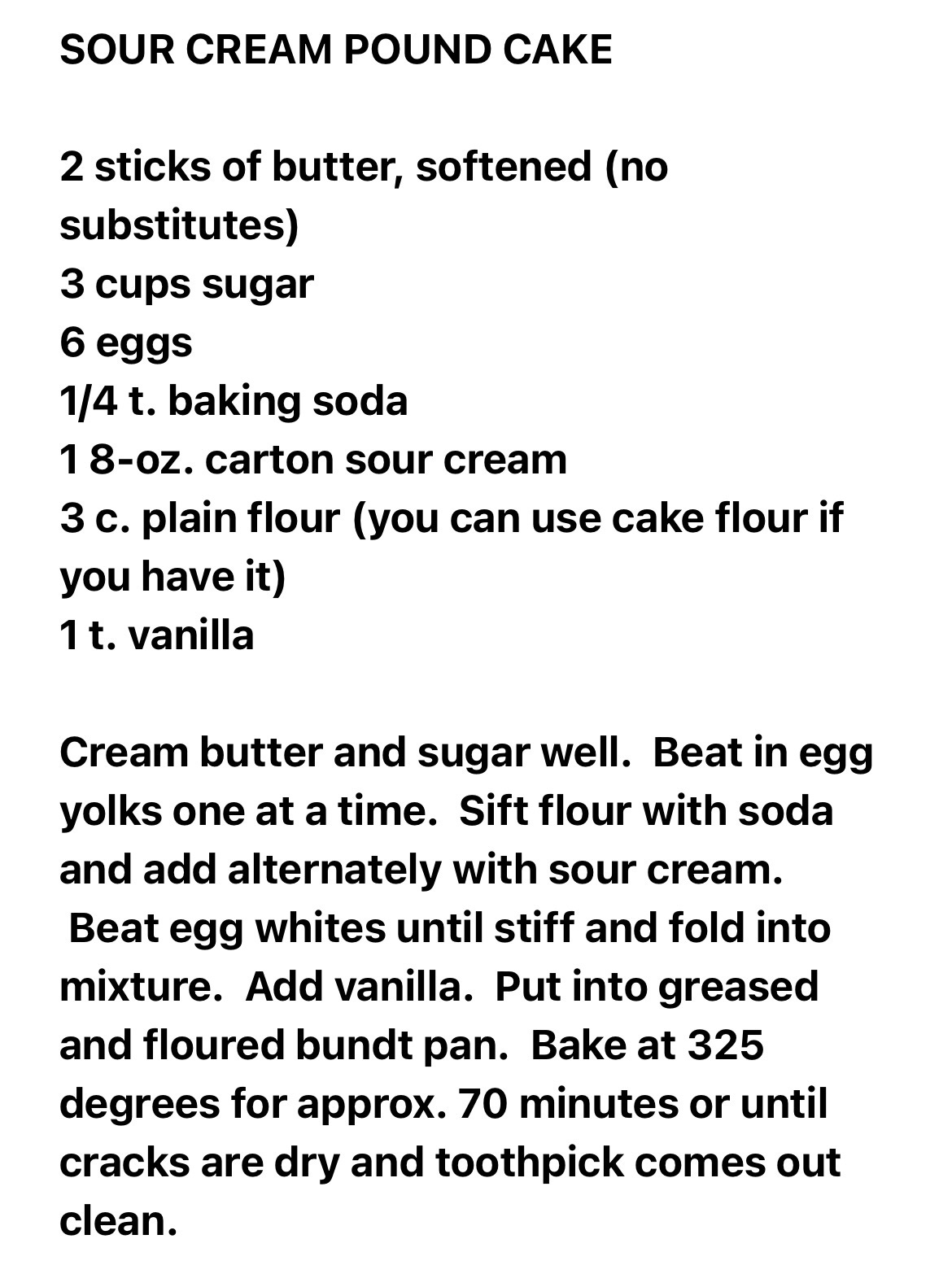

Pound Cake

I don’t like pound cake, but I like this one… well, when it is warm and suffocated by homemade whipped cream3 and sliced strawberries.

My mother-in-law sent the recipe to me in an email 13 years ago, and for 13 years I’ve just been pulling up that email and using it to remake the cake for my husband’s birthday. Here’s the screenshot of that email. You’re going to want to save it.

And here’s my husband on his most recent birthday. Just because the pound cake is so pretty (to say nothing of those biceps).

Shrinking (Apple TV)

Jason Segel’s character is a therapist (“Shrinking”… get it?)—but when his wife dies, he realizes he is emotionally withering (“Shrinking”… get it?) and could use some help himself. He is a pathetic dad, has no boundaries with his patients, and has abandoned his best friend. He’s falling apart.

The first couple episodes are a little sad, but hang in there because the show gets progressively funnier. And, I have never wanted to be friends with anyone as much as I want to be friends with the Gaby character. The way the show writers wrote in the detail of her always carrying around (and refilling) an absurdly large water bottle slays me. Like hydration is her whole, glorious personality.

Tied for the best show currently on television IMO. (If you want something gritty and intense—like what happens when everyone really, extremely needs therapy—watch Succession. If you want something funny and heartwarming—like what happens when everyone, mercifully, gets therapy—watch Shrinking. But obviously watch them both.)

Are Helicopter Parents Actually Lazy? by Kathryn Jezer-Morton

I’ve been recommending

ever since I stumbled on her Substack ages ago—which I believe sprung from her disseration research on momfluencers, and which has now moved to a column at The Cut. I find Jezer-Morton to be whip smart but also generous and thoughtful (oh, the rarest of combinations!).4Here she’s considering the “helicopter parent,” a modern role we supposedly mock but actually often internalize as the “best” way to parent. The idea behind the hovering parent model is that, if I’m not constantly ‘advocating for’ my child (i.e. sending emails to teachers on their behalf, volunteering for every school function, making food art for their bento-box lunches), it’s because I don’t make/have enough time to do so. Mothers may laugh at the idea of helicopter parents in general, but most also take a bit of pride (and harbor a bit of smugness) when they do offer high levels of involvement.

It’s easy for me to make the argument that helicopter parenting is detrimental in the long-term for a kid, but this article teases out a vaguer sense I’ve had: that coddle-parenting is not only damaging but maybe also… easy?

In other words, maybe it’s not a question of how much involvement but rather which type. Although benign neglect on a Saturday (in the form of, say, “I’ll be here reading my book; go have fun”)5 ideally results in kids making forts out of tree branches in the yard, that kind of parenting takes at least as much energy and patience as outsourcing kids to all the premiere weekend activities.

An excerpt:

I also wonder if we misunderstand some of the motivations for helicopter parenting. We assume it’s an anxiety response, and I’m sure that explains a lot of it, but it’s also the path of least resistance. I’m not one to call people out for being lazy — in Montreal, we prefer to call it “l’art de vivre” — but I might have to make an exception here.

“Sometimes it’s harder to parent your kids to become independent than it is to helicopter — it can be exhausting, and it can be time-consuming,” said Dr. Gail Saltz, clinical associate professor of psychiatry at New York-Presbyterian Hospital and host of the How Can I Help? podcast. As counterintuitive as it may seem, letting kids make mistakes, and being there to support (and clean up after) them, can be more work than doing everything yourself. “Your kid will leave the house with their shoes on the wrong feet, and you’ll think, The teacher’s going to see this; what will they think?” said Dr. Saltz.

“Nuance is the refuge of the hopeful.”

— Russell Worth Parker (here)

As always, it’s good to end with hope.

literally always

A huge pet peeve of mine is when the podcast host speaks more than the guest. Tippett is a master of offering, instead of pre-formed responses, merely a tender “mmm, yes,” and I sometimes hear that Tippett-style lilt playing in my head while listening to people talk IRL.

Beat some heavy whipping cream real fast. Add some powdered sugar and vanilla, doesn’t really matter how much. Easy and very “worth it.”

Don’t have kids? Don’t give a hoot about parenting? Doesn’t matter. I’m just as interested here in (a) the way our parenting models are extensions of a cultural (likely Western) reliance on [the illusion of] control and (b) what these models tell us about how we as a culture deal with [or don’t deal with] life’s baked-in anxiety. It’s really less about the kids here than it is about the adults. About all of us.

I learned this from my father, whose preferred phrasing when we asked “what to do” was “Go pour sand in your head and pick it out.”

Love how you’ve formatted this! Book especially sounds good!

Really loving this new roundup and presentation, Lindsey! Looking forward to number three.