Artists—especially artists who are mothers—learn a skill early on, one that has nothing to do with brushstrokes or sentence structure or note sequences.

They learn to protect their hours.

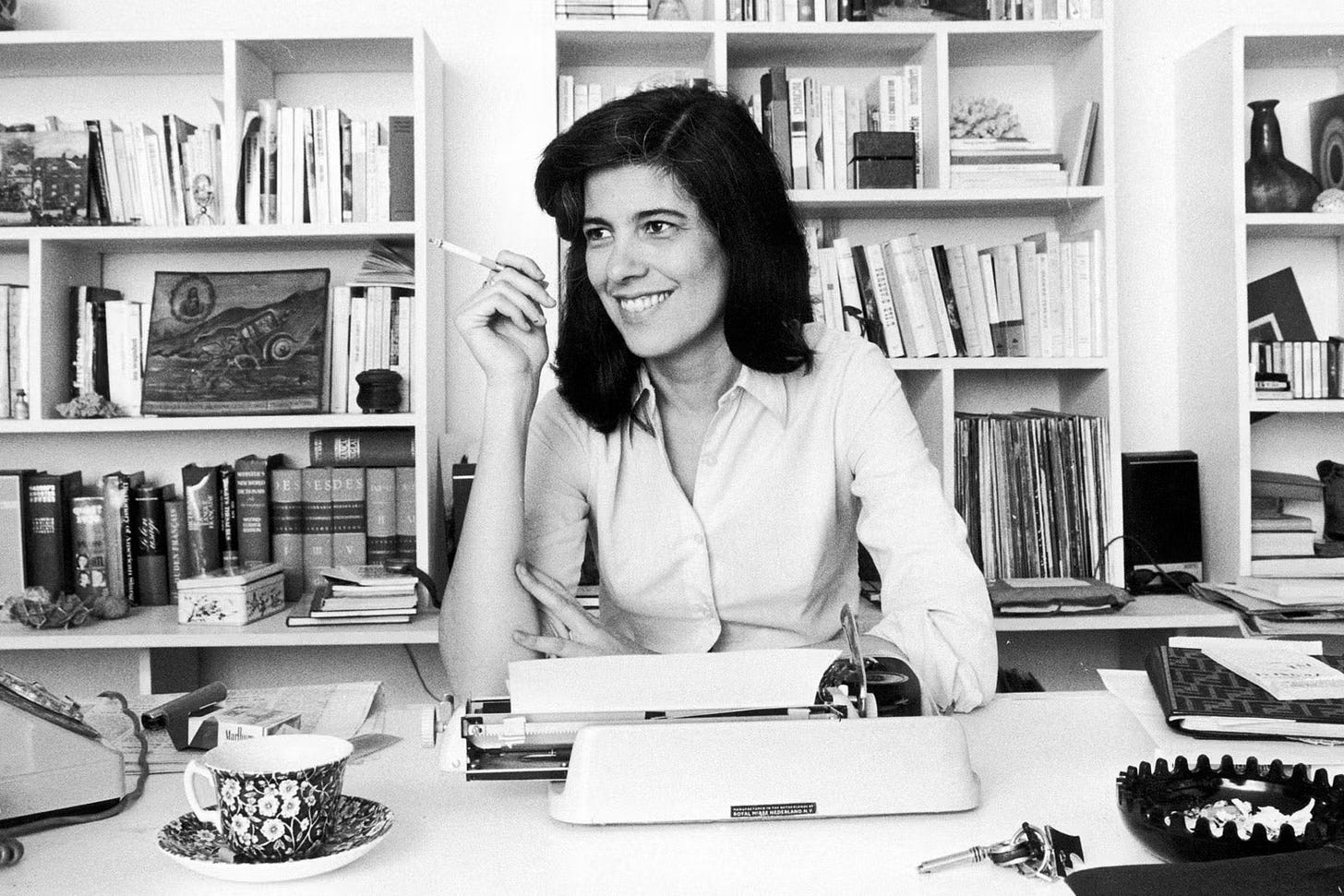

If you read the writings of female artists,1 as I very often do, this theme recurs over and over. Novelist Louise Erdrich once said that women writers ‘must often hold their mates and families at arm’s length or be devoured.’” Writer Susan Sontag argued that what the creative self really requires is “not being too generous with one’s emotional labor.”2

I disagree, in a sense (there are worse things than being devoured), but I know the dilemma well. This week, I am preparing to take a painting class my friends gifted me last summer for my 40th birthday. Every day this week, I’ve tried to make progress on gathering my supplies, prepping my canvases, and reading the class instructions. Every day, I find tubes of paint under the kitchen table, or an expensive new paintbrush commandeered by an eight-year-old, or my supply list in the trash can under a banana peel. Standing in the kitchen exhausted, I raise an open bottle of turpentine and shout, “Just making sure no one drank this?”

At least one million times, I have thought, “This class is not worth the effort.”

It requires a mighty conviction to press on. To “protect one’s hours” goes beyond claiming time to do The Thing: to write or paint or woodwork or mountain bike or play the tuba. It goes beyond making a frightening sign that says “DO NOT MOVE THESE THINGS” and duct-taping it to the pile of paint supplies.

We are too weak-willed to protect our hours, and the cultural resistance is too mighty. If we are going to do it, we have to first conduct a far deeper analysis about what matters to us—and what doesn’t matter enough.

Every so often, for years now, I’ve been making lists of what matters to me. Which is to say, I write “WHAT MATTERS TO ME” at the top of a piece of paper and then think hard about what I want to write down.

My most recent list is full of “-ing” words: making, painting, writing, editing, teaching, reading, walking, running. I made this particular list to help me decide if I want to apply for a particular job. Because to decide how to spend my work hours, I have to also consider how to spend my free hours. The equation is 24 hours = x + y + z, and I have to plug in variables until it works. Or I have to at least get clear about which variables I’d like to plug in. That’s what the lists are for.

For example, if I am committed to working 20 hours/week, would it make more sense to be teaching or writing freelance articles or editing manuscripts? When I have free hours, would I rather spend them watching a YouTube tutorial on photographic composition or reading a book? Of those books, how many hours do I want to spend reading for analysis/learning versus for pleasure? When I have time to exercise, do I want to run on a treadmill or join a weights class at the gym or go for a slow walk in my neighborhood?

It seems so extraneous, this list I make. Of course I shouldn’t have to write down “family” to know my family matters to me.

But it’s not so much what appears on the list that affects me; it’s what doesn’t appear on the list. I do not write things like television, which I watch most nights. I do not write volunteering at the kids’ school, which I am asked to do literally five times a week. I do not write cleaning out my car, making my kids’ lunches, or ironing anyone’s clothes. Nothing shows up on the list about me attending parties (something that would surely show up on my husband’s list) or waiting for my kids at their own friends’ birthday parties, which could easily swallow an entire weekend.

It seems, once I’d made the list of “what matters” a time or two, I should be able to predict what would end up on it. Not true. There are some obvious firsts; but beyond that, I have no idea how I might want to order things, and the order changes every year. Perhaps this sounds tedious to you. Perhaps it seems like practical work. But no, this is not scheduling or time management. What I’m talking about is soul work.

Maybe, a person less full of wants does not have to make these lists. Maybe I am the only one who gets in a panic thinking about how many things I’d like to do and will never have time for. I would like, for example, to have one lifetime to learn photography and another to learn oil painting. I would like to spend one lifetime with books and another with plants. I’d like to spend a lifetime with my family in which every other hobby and interest falls away. I’d like to spend at least a few lifetimes raising my kids from newborn to seven, then hitting restart and doing that part all over again. In one lifetime, it would just be me and some goats.

But lifetimes don’t work that way. A lifetime is a series of choices between things we must do and things we want to do, things we love and things we merely like, things we want to do a lot and things we want to do only a little and things we want to do not at all.

Annie Dillard said, “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.”

In absolutely zero of my alternate lives am I the President of the PTA.3

Yesterday before 10 am, I had located and wrapped a suitable ornament for my son’s second grade ornament exchange, hunted down a styrofoam sphere for my daughter’s cell model project, stopped into the post office for special holiday stamps, and hid gift deliveries in my closet.

I’m on a bunch of text threads with school moms, which always ramp up around busy times like holidays. Moms apologize a lot: for missing events, for sending in suboptimal craft supplies, for misunderstanding the homework. One mom said she couldn’t attend a holiday party, and the response was this: “Well, we can’t do it all! My motto this year is ‘good enough is good enough.’”

At first, this is a refreshing take. Yes, let’s all relax. Let’s be content with being just shy of perfect: good enough.

But I haven’t been able to stop thinking about the exchange. Implicit in the response is some kind of failure, the suggestion that we should forgive ourselves for a goal not met. Of course we’d like to go to all the parties, buy all the best ornaments, attend all the school events. Of course we should. But because there is only so much time in the day, or dollars in the wallet, or units of energy, we can’t meet the ideal.

What if it’s not the good enough part that’s problem? What if it’s the ideal itself?

In other words, do we want to attend all the concerts and parties, make all the cookies and crafts, help with all the homework and projects? Is it really ideal that we volunteer with choir and book fair? Should we even want to want to? Is all that doing even good for my kids, or the earth, or anybody?

I should say: The supposed ideal changes as phases of our lives change. At the moment, my supposed ideal has a lot to do with diced fruit and fifth-grade math strategies. If you’re not a parent of youngish kids, try to take the kid-related details out of the issue. The point is just the question: How much of what you’re doing really aligns with what you say matters to you?

My soulmate4 Oliver Burkeman wrote this:

“Convenience culture seduces us into imagining that we might find room for everything important by eliminating only life’s tedious tasks. But it’s a lie. You have to choose a few things, sacrifice everything else, and deal with the inevitable sense of loss that results.”

Choose a few things. You only get, like, five.

One hand of things 🖐🏻 can matter to you.

So yeah. There is always loss.

Yesterday in the car, I listened to a podcast with the late poet Mary Oliver. She is considered wise by many people (myself included), but mostly what she did was wander around outside and then write down some phrases about it.

Her most famous poem (maybe THE most famous poem?) is about just that. You’ll recognize at least the last two lines.

The Summer Day

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean —

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down —

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don't know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn't everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

In the interview, Oliver said she was once criticized for spending all her time walking around outside. “She must live on a huge grant!” the person said. “She’s rich! How else could she afford to walk around and write poems?”

Mary Oliver laughed. “I was so poor,” she said. “On those walks, I was looking for food. I ate the mushrooms.”

I am obsessed with this response. Take that, sanctimonious critic! The woman was out there EATING THE MUSHROOMS FOR DINNER.

I am also obsessed with Ross Gay’s response in another interview, when he was asked if “looking for delight and joy is for the privileged.” Gay actually interrupts the interviewer to say, “No, no. That is total bullshit. Don’t let anyone tell you joy is a luxury.”5

Do you see?? I’m so sick of living in a world that’s too busy for wisdom. (And if we’re so busy, how come we have so much time to shop?)

To some extent, because of the way we’ve set up our world, it’s absolutely true that not everyone can “wander the fields” (assuming that is a literal task and not a metaphor for finding beauty). But I think, and this is a scandalous opinion, 90% of people could wander the fields, and they never will because they are in love with complaining about their busyness. They claim to be wrapped in the chains of poverty (time, money, resources) when really, they are unwilling to take a loss to do what matters to them. They don’t want to wander “idle and blessed” if it means they have to eat mushrooms.

I don’t literally mean we should all go wander the fields. That’s for poets, I guess.6

I’d rather paint. My list isn’t Oliver’s list, and Oliver’s list isn’t yours. What matters isn’t what’s on the list but that we get fierce about knowing it.

What poets understand is how to do a thing the world tells you is a waste of time. Poets have a lifetime of compulsory practice defending how they spend their hours. I’m not a poet, but I figure, if you’re going to dedicate a lifetime to scribbling words (not even full sentences, I’m telling you!), you’d better have done some of that deep analysis. You’ll need to start defending your choice of major in college and never, ever stop defending yourself. Our era has nothing but disdain for the unprofitable poets.

I don’t think Oliver means what we think she does when she says she “knows how to be idle and blessed.” It sounds trite at first, but I think she refers to a hard-won knowing. To be idle and blessed, to pay attention—she calls this her best version of a prayer.

I love that Merriam-Webster tells me there are two forms of idle: 1. lazy and 2. dormant. These definitions are not shades of the same meaning but practically opposites. Because to be dormant is virtually excruciating these days. It is hard work to make a life that has space inside it.

I don’t mean hours spent scrolling—I mean meaningful space. Time made expansive by intention, not time we lose by accident.

In another episode of this (obviously beloved) podcast, physician Atul Gawande explains that most people don’t question how they spend their time until they are dying. Only when our lives are nearly over do we wish we’d made more time for “walks in the woods,” whatever our version of that might have been. (I suspect most people make it to the ends of their lives without discovering what their version was.)

Of course, by the time we are dying, it is too late to ask the question. Gawande talks about how people realize only as their bodies are truly shutting down—as “walks” become physically impossible—that, only one or two years earlier, they could still have spent their hours doing what mattered to them.

We are told—somehow, by someone—that pausing to ask the questions (to make the list of what matters) at thirty or forty or fifty is frivolous.

This is a lie.

We don’t have control over all our hours. We may have control over very few of them. Isn’t that all the more reason to think hard about how we want to spend them? To make choices everyone else considers ruthless?

You may have heard the phrase, “If it’s not a hell yes, it’s a hell no.” My mantra this December is not some resigned “good enough.” It is not some apologetic shrug, some guilt-dripping defense.

My mantra this December is “hell no.”

Without exaggeration, that mantra is the only way I will ever make it to this painting class. Mary Oliver doesn’t footnote herself when she says she knows how to be idle and blessed. She doesn’t apologize in the next line. She doesn’t say, “But you must understand, I was not living on a grant!”

No, Mary Oliver strolled through fields right up until her death at age 83. She understood there is no reward for our miserable hours, the ones spent in martyrdom. And when it was all over for her, when her time watching grasshoppers was up, she was clear enough in what mattered to her to exclaim in defiance:

“Tell me, what else should I have done?”

Yes, actually, I do think this is a problem somewhat unique to women artists. There is a tension inherent in those identities that forces a reckoning of one’s priorities.

These quotations are pulled from the excellent (and fairly academic) book The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem, by Julie Phillips.

The point being: This is **someone else’s version** of time well spent, and that is GOOD. It just isn’t mine.

Intellectually, darling husband.

This is a paraphrase.

Evidence suggests this is almost universally true. Poets love a walk.

Lindsey! You nailed it so hard in this piece. I could've written it myself (albeit not as eloquently). I especially feel it's relevant to creative mothers. Personally, I sacrificed all my creative time for my kids, which made me feel hollow and, dare I say, a little resentful for a while. But it was my choice, so who did I really resent? Myself.

Now that they're older, I'm reclaiming it day by day. I've missed a game. I've chosen to not attend a party. I've sent them home from school with a friend. Little by little, we take it back. And they don't even hate us for it. My kids are getting to see the side of me that was dormant for a long time, and they sort of love it.

A clarion call to do what I was made to do! I will make my list now. And Subscribe. If you can make time (I won't fault you, if not), read this essay I wrote about my parenting failures -- it will speak to you, make you laugh, and, I hope, encourage you. https://open.substack.com/pub/katesusong/p/perfect?r=2iyrll&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true